Greetings, fellow book-bashers!

Today, I’m very pleased to bring you one of my absolute favourite writers on all of Substack —

.Tom writes the absolutely hilarious

, a travel diary about London and afar that never fails to make me laugh out loud. Think less traveller navel-gazing and more awkward urinal encounters.When Tom said he wanted to write about a Bill Bryson book, suddenly it clicked into place for me. The stream-of-consciousness observations and hilarious witticisms in

— they remind me of the great man himself. Anyway, this essay is a perfect homage to both Tom and Bill, settle in for a good read.—

Whenever Bill Bryson has occasion to speak in public, he almost always tells his bear story. The story goes something like this: when Bill was planning to walk the Appalachian Trail, a long-distance footpath in the eastern United States, he became concerned about the possibility of bear attacks. This is not unreasonable as bears do sometimes, for one reason or another, attack.

When it became known that he would be walking The Trail he got letters, as he says, “by the sack-full,” from people who shared his fear. Most people told him that the main thing he should do is go hiking with someone who can’t run as fast as he can. But one woman wrote to Bill to give two pieces of advice: one, that he should wear little bells on his clothing which will warn the bears of his presence and keep them away. Two, that he should look out on the ground for grizzly bear scat, or dung. He’ll be able to tell that it’s grizzly bear scat or dung, because it has little bells in it.

I know this story so well because I’ve seen or heard Bill speak countless times. Not in person, but on YouTube videos and podcasts and radio shows. I’ve watched or listened to these talks or interviews at least a dozen times each because I am completely and irretrievably obsessed with Bill Bryson.

The bear story is very Bill Bryson. It’s not too long, but for its few lines it’s pulling you imperceptibly towards the carefully constructed punchline. You can find this sort of story in pretty much all of his books.

It’s most evident in his travel books, though. Bryson started as a travel writer, though not on purpose. His first book The Lost Continent he saw as a kind of memoir of travelling around his home nation after years of living in the UK. It’s only when he presented a load of ideas to his publisher for the follow up, none of which were travel-related, that his publisher told him, oh no, you’re a travel writer now, you need to write another travel book.

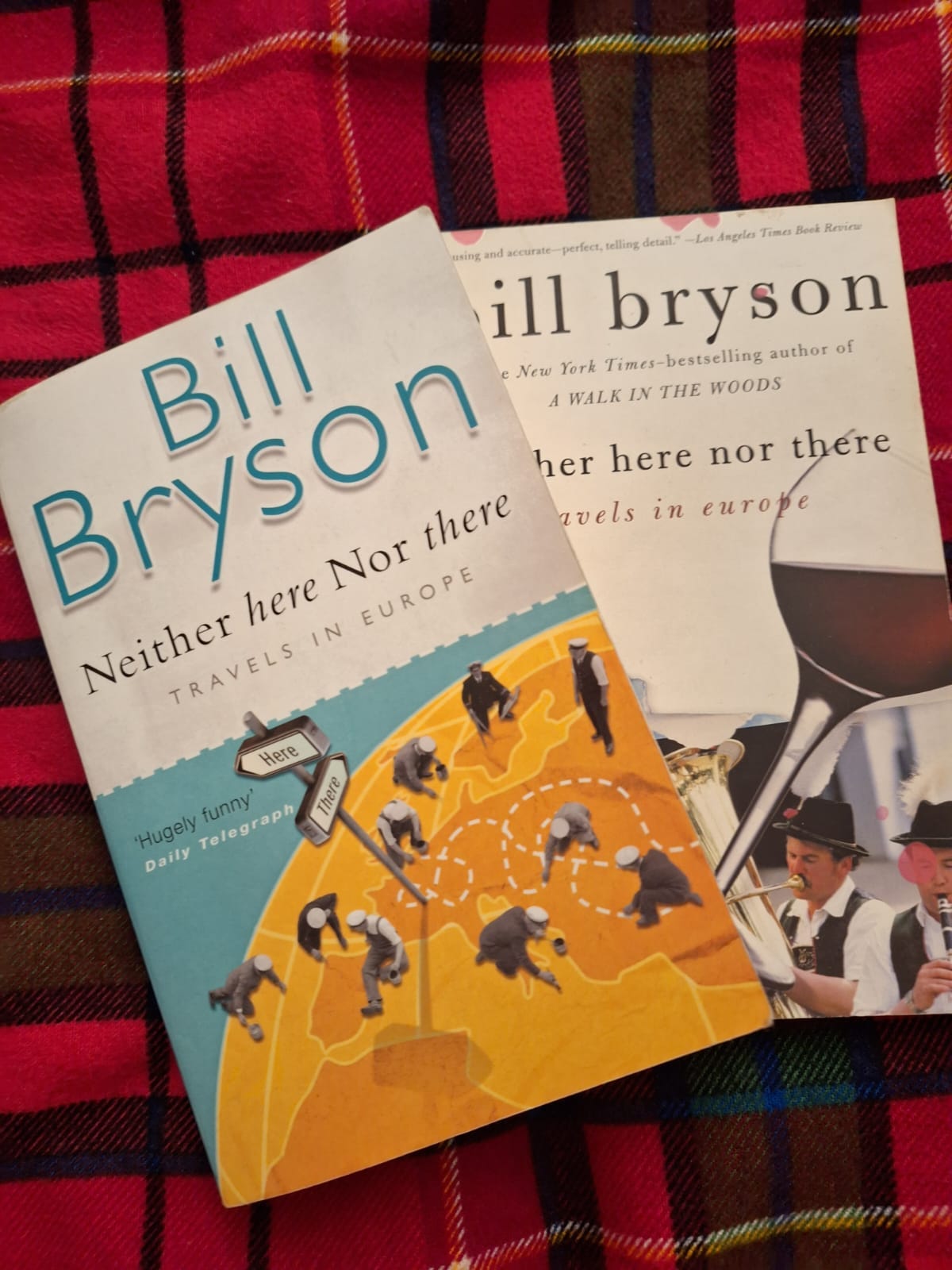

I am personally very grateful for that publisher, because his second book ended up being Neither Here Nor There, Bryson’s account of his travels in Europe. I first read it in my late teens and discovered to my considerable excitement the genre of travel writing.

I had, and have, always wanted to be a writer. An early hobby of mine was making my own newspapers and magazines with crayons and sheets of A4 paper, and then selling them on to my readers – almost exclusively my family – for small change.

And so, when I turned 16 and became aware of such a thing as the “canon” or a group of books people called “classics,” I dutifully set about reading them. The Great Gatsby, A Farewell to Arms, 1984, I read them all and I thought they were brilliant.

But a small part of me thought that maybe I thought they were brilliant because I was supposed to think they were brilliant. I liked them, sure, but they weren’t what I woke up itching to write.

Instead, my head was full of travel plans. I’d first read Bill Bryson’s book on the history of America in 1927, One Summer, and when flicking through to see what else he’d written I stumbled across Neither Here Nor There.

One of the things I like the most about it is that it doesn’t start in Europe’s big cities: London or Paris or Rome, but the town of Hammerfest. Hammerfest is a town at the very top of Norway, and in the winter months the sun is nowhere to be seen.

Bill travels there on an excruciatingly long bus ride and endures the freezing cold, dark days in the town because he desperately wants to see the northern lights. He spends time getting to know the locals and becoming the local eccentric. He stares at the sky for long periods of time. He goes for walks in blizzards. But it’s an ultimately fruitful quest that sets up the book, and of course Bryson does then take in the sights of the more famous European destinations.

He goes to France and thinks the Parisians are rude and that all French drivers want to kill him. I’ve been to Paris many times. I don’t think they’re rude, rather they’re just sick of English people coming to Paris and talking about how rude they are. I’m English and I’m sick of the English, so here I have some sympathy for the French.

I have had experience of French drivers wanting to kill me, but I deserved it. I was trying to get to the centre of the traffic island where the Arc de Triomphe sits, and I hadn’t realised that everyone else had got there via a subway. I waited for the briefest of gaps in the approximately eight lanes of traffic and set off and, predictably, suddenly had about thirty-seven Peugeot’s baring down on me. These particular French drivers wanted to kill me, and I wanted to make it across to the Arc alive and without soiling myself.

Italian drivers might not want to kill Bryson, but they will, probably inadvertently. This is a stereotype so old and enduring that talking about how bad Italian drivers are has become a stereotype in itself. In any piece of travel writing about Italy there is always, always, always the part where the narrator talks at length about the time a Fiat crashed into him or he narrowly avoided a careering Lamborghini.

This stereotype is so old and enduring because it is true. I once spent two nights in Naples a couple of years ago and ever since, every time I see a moped or a scooter, I want to scream and run behind the nearest solid wall. As I walked down Spaccanapoli, a thin street right down the city centre, I was passed by a moped being ridden by a man who was holding a baby. The baby was holding a lollipop. After seeing that particular health and safety inspector’s nightmare I vowed never under any circumstances would I drive a moped on Italian roads.

Finally, Bill has a quite overpowering fear of any restaurants whose menus are exclusively in German. This I won’t have. Currywurst, that most German of snacks, is one of the greatest things you can do with a sausage. Sure, the sausage may have only glimpsed a pig from a distance, once, but I would eat currywurst for every meal of every day if it wasn’t certain to result in something violent happening to my insides.

Neither Here Nor There is not a book then that is a deep dive into European countries and cultures. Do not read this book if you want to find out exactly what it is that makes an Austrian tick. This book is an American man travelling around Europe pointing at things and saying ‘Hey! That’s weird, look at that!’

But it’s funny. Really funny. Not just slightly amusing in the way that might make you smile on the train while reading it. But funny in the way that will make you snort uncontrollably, then tap the man next to you on the shoulder and ask him if you could just read him this passage.

Some of the best parts are flashbacks to Bill’s travels in Europe in his younger days, when he was accompanied by his friend Stephen Katz. If you think Bill is a slightly haphazard traveller, then wait until you meet Katz. Stephen has a more prominent role in the book A Walk in the Woods, when Bryson attempts to walk the Appalachian Trail. But he’s here in Europe too, thoroughly making a fool out of himself.

Bryson is so good he makes reading about his experiences interrailing as a young twenty-something actually interesting, a task that anyone who has had the misfortune of being stuck next to the white guy with dreadlocks at a party will know is extremely difficult.

It changed me because of all the jokes, because it’s funny. It was a revelation to me that a man could write a book so chock full of sentences designed to make people laugh. The fact that the jokes were interspersed with haphazard journeys to faraway lands made it all the better.

Before I read Neither Here Nor There I wanted to be a writer. By the time I had finished reading it, I wanted to be a travel writer. And I wanted to make people laugh. Had I not discovered Bill Bryson, I might still be here on Substack, but I certainly wouldn’t be writing what I do.

And I certainly wouldn’t be able to tell you the bear story. But I can tell you it, word for word, right up until the part with the grizzly bear dung, or scat, with the little bells in it.

P.S. For more ways of getting your writing in front of new readers, consider becoming a paying subscriber today.

So well written. I laughed out loud more than once!! Thank you, M. E., for introducing me to Tom and, Tom, for reminding me of the genius of Bill Bryson. Looking forward to diving into both. :)

Love Bill Bryson. Combines two things I enjoy humor and travel.