Whenever I visit the house of my grandfather, who now lives in a single room of a nursing home, I drop my stuff in the entryway and go straight to the basement, waving a rolled-up newspaper like a wand to clear a path through the cobwebs. Each of the four basement rooms is full of artefacts from his life, and I pass through them studiously like Indiana Jones at an archaeological site.

In one room, there are shelves packed with jars of homemade fruit jam. In another, there’s a military-green metalworking machine and a workbench trembling under generations of tools. The biggest room contains a closet of motorcycle leather, some handcrafted furniture and, leaning against a wardrobe brimming with East German garments, two bikes whose tires have gone flat since my last visit.

Keep in mind this is not an Americanized basement all drywalled and carpeted for comfort. It’s big, yes, but more cavernous than roomy. I have to walk in a shallow bow to avoid scraping my head against a fragment of excavated cliff. It is both crazy and easy to imagine my grandfather hiding out down here as a kid when the Allied bombs came screaming through the sky. So much life took place between these cold stone walls that now doesn’t. When I walk down the dark, damp stairway, it’s to absorb the absence.

Turns out there’s a word for this vibe: Kenopsia. A concoction from the Greek “kenosis” (emptiness) and “opsia” (seeing), kenopsia refers to the “eerie, forlorn atmosphere of a place that was once bustling with activity but is now abandoned and empty” — a deserted movie set, a club the morning after a party, Burj Al Babas, locked down cities, Chernobyl.

Kenopsia was coined in 2012 by John Koenig, whose Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows is full of neologisms for emotions we commonly feel but lack the vocabulary to express. Anemoia, for example, is nostalgia for a time you’ve never known. Lachesism is the desire to be struck by disaster. Meanwhile, Koenig’s most cited invention, sonder – the realization that each random passerby is living a life as vivid and complex as your own – has already moved through the Instagram-caption-to-spontaneous-tattoo-in-Thailand pipeline.

As an aesthetic, kenopsia possesses many of the seductive qualities of liminal space: displacement, longing, ephemerality. But while liminality refers to a state of transition, with a part of its intrigue owed to that which is yet to be, kenopsia’s emotive force emanates wholly from that which is no more. Life has left the room. We can feel it.

On reddit, r/kenopsia mostly features images of physical spaces in various stages of desertion or rewilding, though I’ve felt some of the most potent kenopsia online. Consider the uncanny vibe of an inactive social media profile, or stumbling across the stale pixels of a live thread of 9/11. “I bet the pilot was talking on his cell phone,” it begins. “Bush is going to start nuking everything in sight now,” it concludes. The last post was 22 years ago.

A few weeks ago I happened across my MySpace, a graveyard of broken images and lost connections. The only image that still appears anywhere on my page is the profile photo of Lil Wayne, in my Top 8. I felt vertigo scrolling through names of people I went to high school with but had since forgotten. I’d have to login to sk8_or_die89@hotmail.com if I wanted to change anything.

All my images are gone but their captions remain. “My car ;)” reads one in which I’m leaning against my parents’ Grand Am before a castle in an affluent neighbourhood we didn’t live in. In another, captioned “Raptors Dance Pak!!!,” I remember posing awkwardly with my arm around an NBA cheerleader. It was halftime against the Cavaliers, featuring LeBron James, who was also in my MySpace Top 8. I was there with three of my best friends at the time, two of whom I haven’t spoken to in a decade.

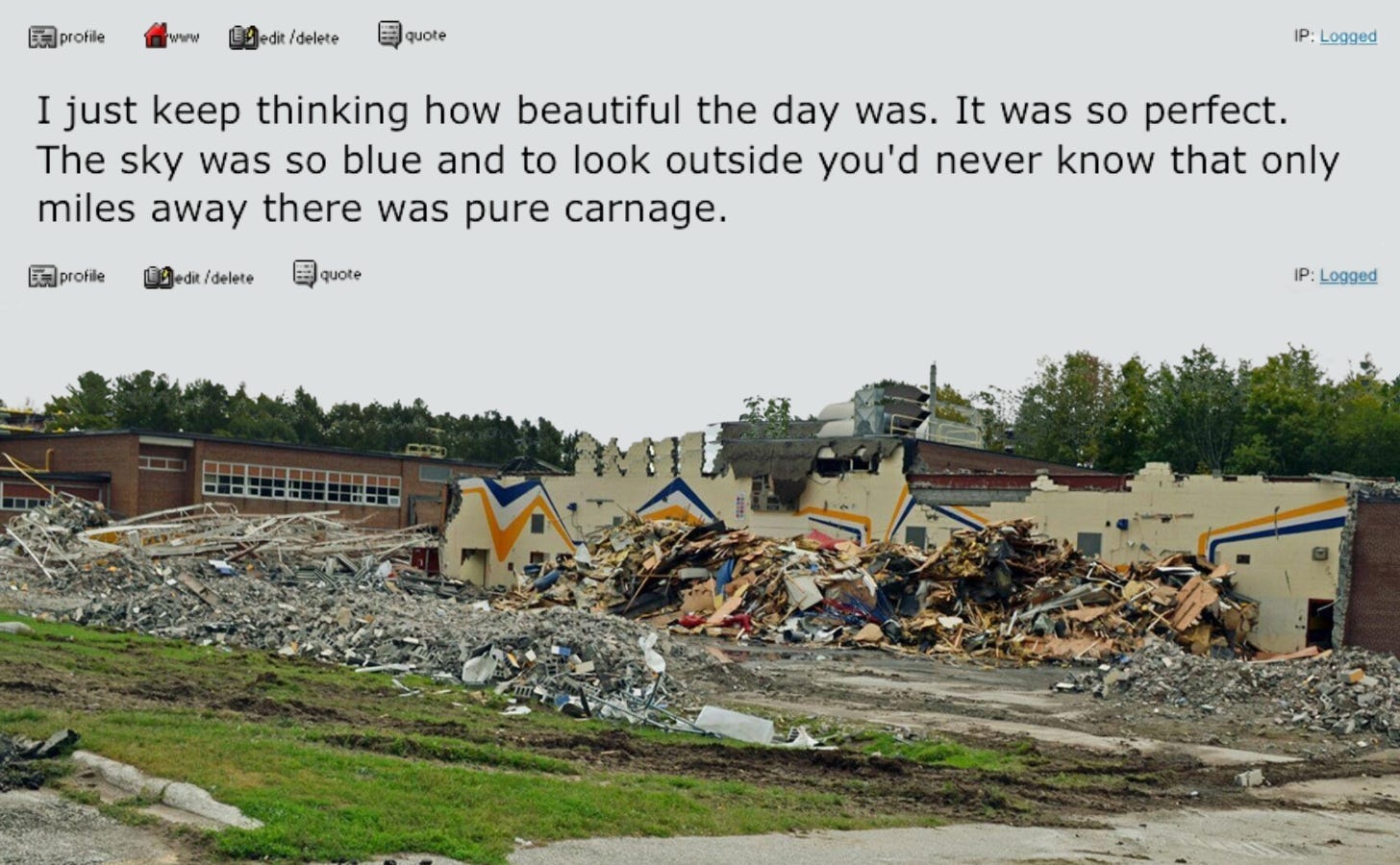

One of those guys, I just checked our Facebook wall. Again that feeling of currents moving in different directions through my head. We talked about eating orange chicken at a food court that no longer exists, going to parties at the house of someone who’s since passed away, and basketball tryouts at our high school, which was demolished in 2019. Layers upon layers of kenopsia.

In Koenig’s conception, what intensifies kenopsia is the “emotional afterimage” of a place, which can “make it seem not just empty but hyper-empty, with a total population in the negative.” By that definition, at no other time was kenopsia so universal as during the pandemic. Entire cities became ghost towns. Engaging with so many architectures of absence – empty restaurants, deserted gyms, barren schools – instilled their own inverted afterimages. For a while, it was jarring to witness the repopulation of places whose empty bliss I’d come to enjoy. It still is. Sometimes I miss seeing how the world looks without us.

In the basement, I sputter and drag my hand over my mouth, having just inhaled a cobweb while distracted by some motorcycle paraphernalia in the far corner of the room with the bikes. The final part of Koenig’s definition for kenopsia refers to a conspicuous absence that glows like neon signs. I consider the incandescence of the inanimate cellar. Even the dust has a lustre. I feel like a moth. This is one space I’d prefer to see repopulated with life.

Love this. It has a nice, spooky feeling. Here is my contribution to the spirit of the essay (although it's not a neologism and not Greek, it is amusing!): Kummerspeck: The weight we gain from emotional overeating. Literally: Grief bacon.

First piece I've read by you. Excellent, Christian.