Greetings, my fellow literature-lovers!

Readers of my other Substack will know that one of my great loves in life is poetry. This is why one of the writers I first pestered about guest posting here on

was , who in my mind is one of the best poets here on Substack.I have my suspicions that Jason may be some sort of wizard because he not only posts wonderfully reflective poems almost every day, but he also accompanies his words with beautiful illustrations he draws himself. I don’t understand how he can produce great art with such profligacy, but I always make the time to read them.

Today, Jason shares how an anthology got him hooked on poetry in the first place.

—

How an anthology got me hooked on poetry

Like most people my age, the education system did a thorough job of killing any spark of interest I may have once had in poetry. The more my teachers droned on about the symbolism of a poem or pulled meanings of lines seemingly out of thin air, the more convinced I was that it was all bullshit.

Then the universe intervened. Miss Taggart was the first salvo in the cosmic battle over my poetry soul. She was the mean English teacher. The one you prayed you didn’t get, the one helicopter parents pulled their kids from, the one who would actually fail you for not doing satisfactory work.

I was a chronic underachiever, indifferent to my classes but deeply curious about the world. For reasons I will never fathom, Miss Taggart took an immediate liking to me. Whatever the reason, she introduced me to Emerson, Thoreau, and the Transcendentalists in her American Literature class, and my mind was blown.

The second salvo was in the form of the popular movie Dead Poet’s Society. I had missed the movie when it was released in theaters right before I entered high school. But it was released on video cassette right as I was learning about Thoreau in American Literature.

Before the school year ended, Miss Taggart mentioned to me in passing that if I really wanted to understand Emerson, I needed to read his poetry. She told me not to read poetry like we do in school. Forget trying to understand what Emerson was trying to say. Ask yourself instead what Emerson makes you feel.

The fateful, final third blast hit early that summer. I found a flyer for a paperback, non-fiction book club. It was like the BMG and Columbia House schemes I was already using to amass my CD collection.

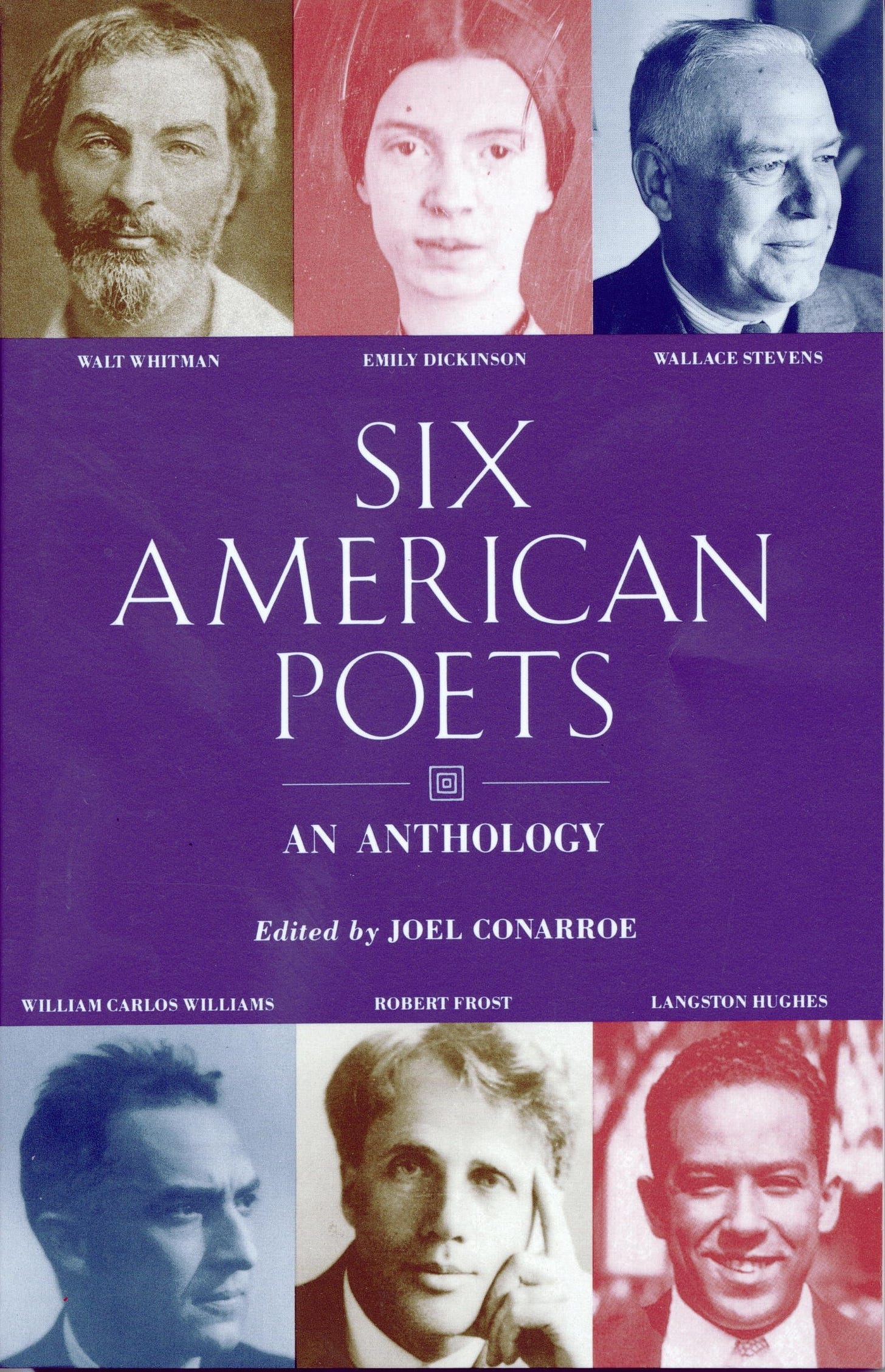

I scanned the thumbnails on the back of the flyer, trying to find six books worth my time. I only remember three of the books I chose. I ordered a massive tome having to do with the timetables of history that was outdated the moment it arrived on my doorstep; Biodiversity by E. O. Wilson1, a fabulous book that made biology and ecology interesting for the first time for me; and a plain yellow book with the title, Six American Poets, An Anthology, edited by Joel Conarroe.

I have no idea what happened to the history book, Biodiversity, or the other three books. But, Six American Poets is right beside me on my desk.

When I cracked open that book at age fifteen, I knew I was on the precipice of discovery.

The book is organized with an introduction, a brief biographical sketch of each poet, and then a selection of poems following each sketch.

I did not then, and have not ever, read the book in any organized manner. Instead, I made a casual decision that moved my life onto a different track. I flipped through the book like a magazine and stopped only at poems with interesting titles or in places where the universe felt it was critical for me to discover something.

Reading poems by these six poets in this way made the poems interesting. I wasn’t studying them. I was feeling them. It was more like listening to the radio than studying a poem in school. At different points in my life, I would read the poet's biographies and the introduction. But the poems themselves remain the main attraction.

I created nicknames for the poets. Walt Whitman was Uncle Walt. At first exposure, his poems were thick, dense, and mostly beyond my imagination–but I loved the way the words echoed around in my head. When I first read the opening to I Sing the Body Electric, I shivered in the California summer heat and felt as if I was being pulled into a portal that would lead me to another realm.

I sing the body electric,

The armies of those I love engirth me and I engirth them,

They will not let me off till I go with them, respond to them,

And discorrupt them, and charge them full with the charge of the soul

I had no idea what the hell any of that meant. I had never heard the words engirth or discorrupt before. But, by god, I wanted to feel the full charge of the soul. It was clear to me that Uncle Walt wrote like the kind of raving lunatic I wanted to go to a punk show with.

Emily Dickinson was Em to me. As a goth-adjacent kid, her fixation on death and love as being intertwined seemed like gospel. In Poem 77, I felt she understood what it was to feel trapped in suburbia.

I never hear the word “escape”

Without a quicker blood,

A sudden expectation,A flying attitude!

I never hear of prisons broad

By soldiers battered down,

But I tug childish at my bars

Only to fail again!

Em seemed to know what it was to be odd, confident in your own intellect, and woefully cognizant of your own significant shortcomings.

Wallace Stevens was Wally to me. He is often called the critic’s poet, and his poems felt cold and clinical to me. At fifteen, his poems only inspired me to flip the page to something else. Now, I see the beauty in Stevens’ meticulous verses. I also find inspiration in his biography, he was a wealthy banker and brilliant poet, showing great art doesn’t require great misery.

The next poet in the book was William Carlos Williams, or Will Squared. Will had seen some stuff too. I could tell. He wrote interesting stories about what most people thought of as boring New Jersey. I highlighted his Complete Destruction, as being meaningful because, at 15, I was going through some things.

It was an icy day

We buried the cat,Then took her box

And set match to it

in the back yard.

Those fleas that escaped

earth and fire

died by cold.

Robert Frost, or Bobby F to me, was the poet I was most familiar with then. I thought his poems were of the same cold, stuffy stuff as Wally’s. I liked the classics, Stopping by the Woods on a Snowy Evening and The Road Not Taken (which featured prominently in Dead Poet’s Society). But I skipped over most of the rest until I found Fire and Ice.

Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice

From what I’ve tasted of desire

I hold with those who favor fire.

But if it had to perish twice,

I think I know enough of hate

To say that for destruction ice

Is also great

And would suffice.

This poem by Bobby F felt resonant with the Depeche Mode, The Cure, and Smith’s lyrics I was listening to almost non-stop that summer. For the first time, I began to consider that what I felt so deeply at fifteen might be universal and not just a result of my peculiar trauma.

The final poet in this anthology would be the one that would dare me to write poetry. Langston Hughes felt too gangster for a nickname. I simply called him Langston. From the first line of his that I ever read, I saw that poetry could make you feel like dancing. How you not help but move your body when you read Dream Variations?

To fling my arms wide

In some place of the sun,

To whirl and to dance

Till the white day is done.Then rest at cool evening

Beneath a tall tree

While night comes on gently,

Dark like me–

That is my dream!

To fling my arms wide

In the face of the sun,

Dance! Whirl! Whirl!

Till the quick day is done.

Rest at pale evening…

A tall, slim tree…

Night coming tenderly

Black like me.

Langston was the poet who lived the life most different, almost incomprehensibly different, from mine. But his poetry helped me bridge the gap. It was Langston, as much as it was The Beastie Boys or Run DMC, that would open my eyes to the fifth dimension, which was hip-hop.

I’m forty-seven now, and unlike my fifteen-year-old self, I’ve really seen some stuff. I own a lot of poetry books, including a leather-bound collection of all of Robert Frost’s work, but nothing gets me out of a funk faster than flipping through the worn pages of the more than 30-year-old paperback.

If you hated poetry in school, I beg you to give it another chance. I give you the same advice Miss Taggart gave me, don’t read to understand. Read to feel. Get yourself a poetry compilation or anthology and start flipping the pages like you would a magazine, and let the universe take you where you need to go.

I promise you’ll wind up somewhere special.

If you’d like to write for The Books That Made Us, please see here. For more ways of getting your writing in front of new readers, consider becoming a paying subscriber today.

I recently finished a graphic novel adaptation of Wilson’s memoirs, Naturalist, which is an outstanding read if you are curious about the intellectual history of scientific environmentalism or if you just love ants, the outdoors, and great storytelling.

I love that book! I have a version without the dust jacket that I must have picked up at a used bookstore or library surplus sale. Not sure exactly how it made it to my shelf, but I've treasured it ever since. William Carlos Williams and Langston Hughes have always been at the top for me, but this made me fully respect and appreciate those other icons...even Wallace Stevens, who I still have trouble grasping. A side note: we read "Fire and Ice" in my high school English class on the morning of 9/11, so it's always had an eerie resonance. The anthology most dear to me is SING A SONG OF POPCORN, a book of children's poetry illustrated by a bunch of Caldecott medal-winning artists. I don't think I'd still be writing or drawing today without it.

Applause! love this so well. Thank you

…I live

in each letter that is

where you will find me.

They have been given

to us as keys to the great

breathing hope of life.

I always wanted to live

there but couldn’t live

there until the poetry

gave me life of words.

-Hannah Emerson

The purpose of poetry is to restore to mankind, the possibility of wonder. ~Octavio Paz