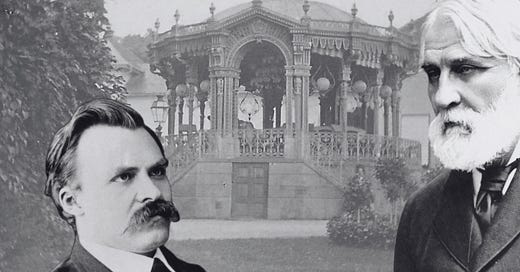

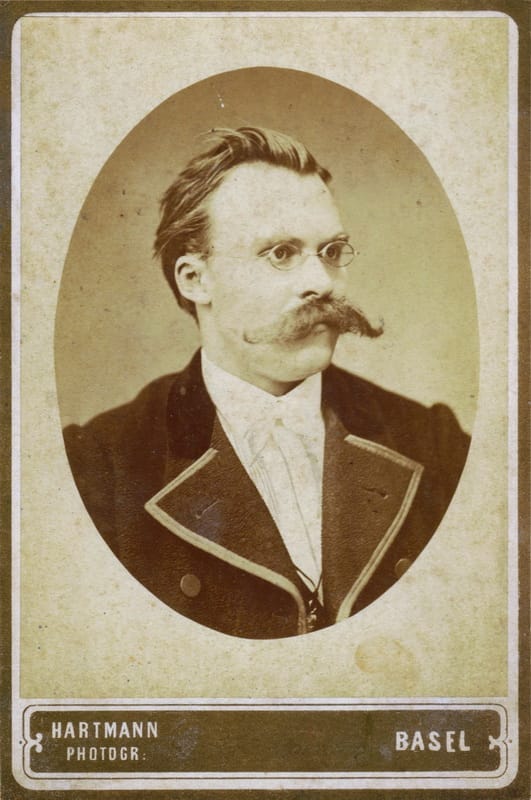

Their eyes met. Before Ivan Sergeyevich stood a young man of unremarkable physique, but with a remarkable set of features above the shoulders: short hair combed back, a high forehead, piercing deep-set eyes behind elegant spectacles, and bushy, almost grotesque moustaches — or rather, the moustachiest of all — which, in the complete absence of a beard, commanded all attention.

The stranger extended Ivan Sergeyevich's walking stick, which he had picked up from the ground, nodded politely, and continued on his way through the park, while Ivan Sergeyevich and his companion, who held him by the arm, watched the young man depart. Releasing his arm, Turgenev leaned on his stick and, frowning —whether from the waves of pain in his knee or from the bewilderment brought on by this chance encounter — inquired:

—What of his beard?

In response, his companion merely shrugged. Baden was being consumed by autumn; the year 1871 had entered its phase of decay.

This encounter might have transpired thus, or it might not have occurred at all, which is most likely, though it contradicted all the notions of the man who had so persistently attempted to arrange it. This unknown individual, a certain Monsieur A, as we shall continue to call him (for we possess no other information about him), fervently dreamt of this meeting, being an admirer of both—the literary giant and the rising philosophical star. Why, wherefore, and how — it is difficult to say offhand. We have only the diaries of Monsieur A and the letters of Turgenev and Nietzsche from that period, which, though not few in number, can hardly be called exhaustive. Nevertheless, we shall attempt to reconstruct the chronology of events and answer all these questions through them.

Beginning with why, let us answer — because of nihilism, what else? It is generally accepted that Ivan Turgenev popularised the term in his novel of 1862, "Fathers and Sons", nine years prior to the events we are investigating. Before him, the term "nihilism" had already been used for many centuries in slightly different meanings, from denoting heresy in the Middle Ages to the pejorative definition of value - destructive tendencies of modernity in the times preceding the French Revolution, later in German philosophy, and still later in Russia, gradually acquiring its final form until Turgenev finally cemented it in the collective consciousness in its current meaning.

The nihilistic characters of the novel, including its main protagonist Yevgeny Bazarov, a nihilist who rejects almost all values accepted in society, both liberal and traditional. Bazarov is a vivid representative of the youth of the second half of the 19th century. He is an intelligent, ironic, sardonic man. He does not recognise art, preferring science, cannot admire nature, considering it a "workshop", scorns romance, and does not believe in love.

Thus, for example, characters describe Bazarov in the fifth chapter of the novel:

—What is Bazarov?—Arkady smiled.—Would you like me to tell you, uncle, what he really is?

—Pray do, nephew.

—He's a nihilist.

—Hows so?—inquired Nikolai Petrovich, while Pavel Petrovich lifted his knife in the air with a small piece of butter on its tip and remained motionless.

—He's a nihilist,—repeated Arkady.

—A nihilist,—said Nikolai Petrovich.—That's from the Latin, nihil, nothing, as far as I can judge; consequently, it signifies a man who... who accepts nothing?

—Say, “who respects nothing,”—put in Pavel Petrovich, and he set to work on the butter again.

—Who regards everything from the critical point of view,—noted Arkady.

—Isn't that just the same thing?—asked Pavel Petrovich.

—No, it's not the same thing. A nihilist is a man who does not bow down before any authority, who does not take any principle on faith, whatever reverence that principle may be enshrined in.

—Well, and is that good?—interrupted Pavel Petrovich.

—That depends, uncle. Some find it good, and some find it very ill.

—Indeed. Well, I see it's not in our line. We are old-fashioned people; we imagine that without principles, taken as you say on faith, there's no taking a step, no breathing. Vous avez changé tout cela. God give you good health and the rank of a general, while we will be content to look on and admire, messieurs... what was it?

—Nihilists,—Arkady said, speaking very distinctly.

—Yes. There used to be Hegelists, and now there are nihilists. We shall see how you will exist in void, in vacuum; but now ring, please, brother Nikolai Petrovich; it's time I had my cocoa.

Ivan Turgenev himself was not a nihilist, rather the opposite, but this did not prevent the fashionable and popular Russian nihilistic movement from appropriating the new name after the publication of the novel.

Later, Friedrich Nietzsche would use the same term in his works in various ways, with different meanings and connotations, including to describe the decay of traditional morality in the West, expressed in the "death of God".

Nietzsche characterised nihilism as the deprivation of the world, and especially human existence, of meaning, purpose, comprehensible truth, or essential value with the decline of Christianity (this, of course, if put in a nutshell). He approaches the problem of nihilism as a deeply personal one, stating that this predicament of the modern world is a problem that has "become conscious" in him. According to Nietzsche, only when nihilism is overcome can culture have a true foundation for flourishing. He wanted to accelerate its arrival only to also accelerate its final departure.

Thus, "passive" nihilism is resignation to the decomposition of old values, while "active" nihilism is a destructive driving force, predestined to build something new from a clean slate, a kind of "free spirit". In other words, active nihilism can be viewed as a necessary stage emerging from all-consuming passive nihilism.

Turgenev's Bazarov is rather an active nihilist who sees in negation a useful, and in theory even creative force. In reality, or rather in the reality of the novel, the principles that Bazarov set for himself prove to be unviable. Denying love and calling it nonsense and folly, Bazarov himself finds himself in love with Odintsova. Thus, gradually, not only the readers but also Yevgeny Bazarov himself become convinced of the imperfection of views and the inconsistency of the nihilistic theory of the main character.

Looking at the situation from the twenty-first century is easier, because we can clearly trace how nihilism transformed after Turgenev's novel, and what form Nietzsche's ideas took. But if we return to 1871, to the time when Monsieur A was trying to arrange a meeting between these two, the answers to the questions of why and wherefore cease to be obvious.

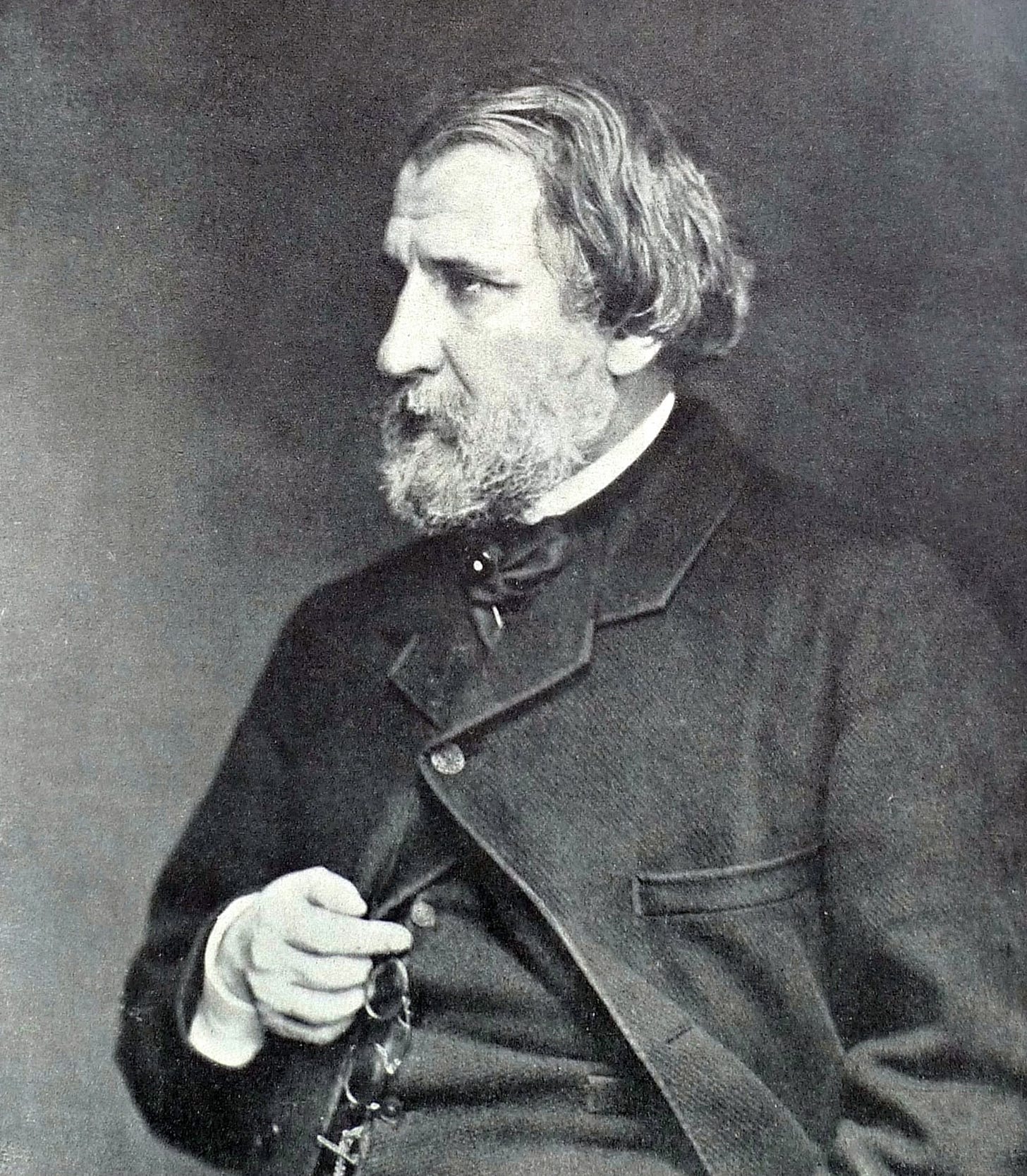

Turgenev at that time was already undoubtedly a well-known person and an established man of letters. He had already spent many years travelling around Europe, was one of the first to popularise Russian culture in the West, both translating works of Russian authors into German and French himself and promoting their translation and advancement, gave lectures, befriended many European intellectuals of the time, including Mérimée, Flaubert, and Sand, acting as an influential figure on the European literary scene.

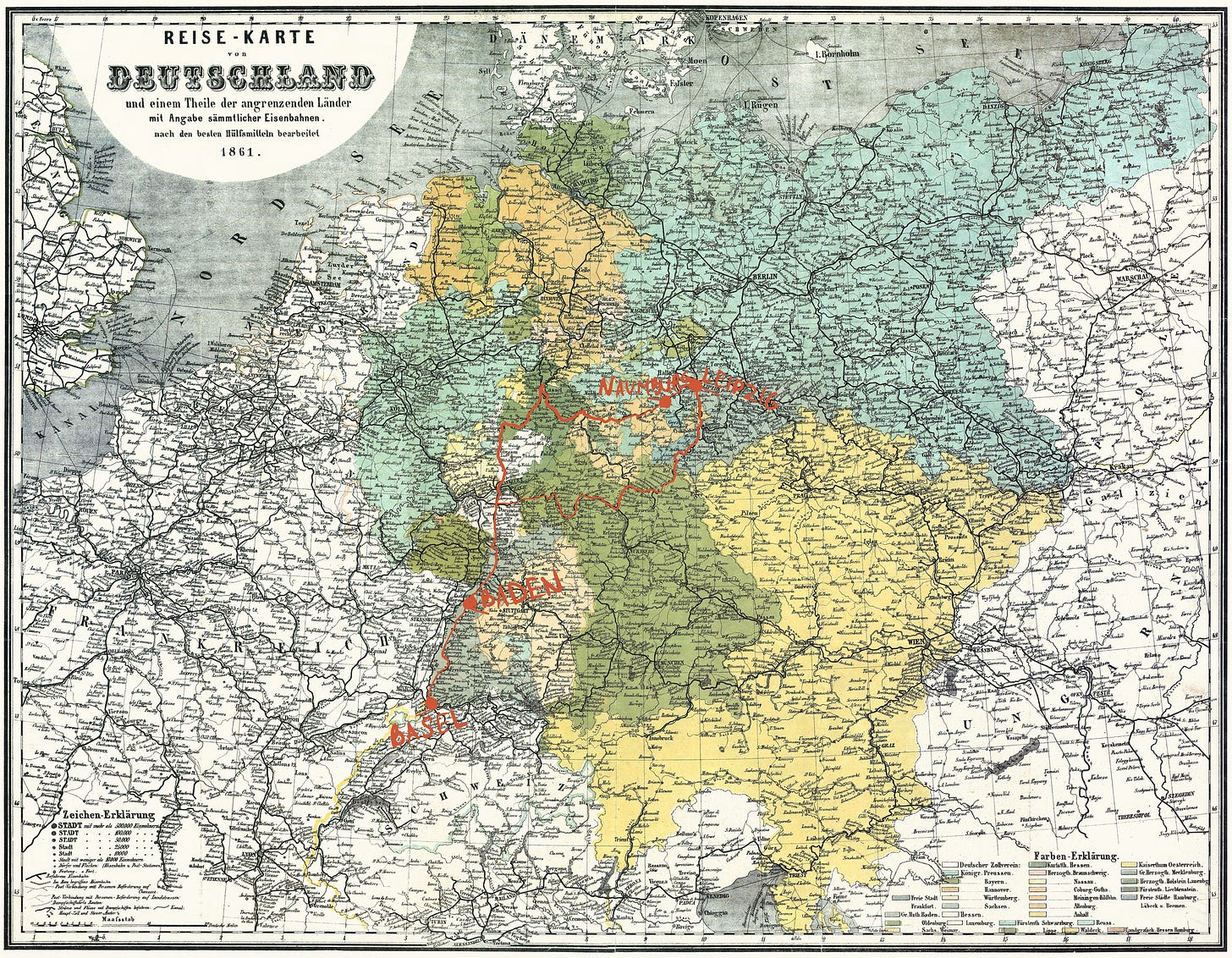

Nietzsche, though the status of a key interpreter of nihilism and worldwide fame were still ahead, at twenty-seven had already been a professor of philology at the University of Basel for a couple of years, which undoubtedly could, and most likely did, attract the attention of Monsieur A. This leads us to think that Monsieur A had connections in both literary and academic-philosophical circles, lived, perhaps, in southern Germany or Switzerland, and, judging by his letters, had certainly been both in Baden and in Basel and was acquainted with both subjects of our investigation.

In his diary, an entry from August 14, 1871, Monsieur A writes:

The only significant talent of mine, which both I myself and those around me recognise, is perhaps the ability to introduce great acquaintances to promising ones, so that the latter might become the former, and as many stars as possible might shine on the European intellectual firmament.

I feel, rather no—I consider it necessary to bring T and N [Note: this is how, presumably, Monsieur A refers to Turgenev and Nietzsche] together while only 90 miles separate them! They are, from my point of view, "father and son", in the true, cultural sense of these words. The son is still young and full of energy and ideas, while the father, though immeasurably wise and influential, is still mortal, like all of us.

If you wish, you may call this a mad hunch, like that experienced by inveterate gamblers losing their entire fortune, or intuition, or anything else that has no facts, figures, premises, proper logic behind it, but, believe me, these things are not needed, for, unlike inveterate gamblers, in the case of a collision of two minds, no one loses, except, perhaps, opponents of the rapid development of thought.

This moment will be a turning point, and I will be the man who created the crack.

To think properly, at least two are needed, at most—several. Write this on my tombstone.

The end of 1871 was in indeed a turning point for all of the characters of our investigation.

Turgenev at this time was in Baden-Baden, suffering from gout, which prevented him from leaving for Paris. He actively mentioned that in his letters from that time. Thus, for example, in a letter to P. V. Annenkov, a famous literary critic, from September 2, Ivan Sergeyevich wrote:

I am writing to you, my dear Annenkov, from my bed, to which a severe attack of gout has nailed me. This time this katkovka has taken it into its head to settle in my knee, which deprives me of the ability to move. One must arm oneself with patience!

The weather is so wonderful—both here and, according to your words, in St. Petersburg, that I venture to write to you at your dacha {I cannot write to the dacha address—for in your last letter there stands only: Lesnoy—and there is no name of the dacha. I cannot go downstairs—and therefore I write through Stasyulevich.} address in the hope that you have not yet returned to the city. I have already written both to London and to Edinburgh about sending me letters, books, etc.

Or, for example, two weeks later to N. A. Kishinsky:

For 10 days now, I have been lying in bed due to a severe attack of gout — only from today it seems to have eased somewhat.

I regret the poor state of the weather; here too we have no rain at all; but I am comforted by your assurance that the income will not diminish much.

I do not need money urgently now, I do not need it; but arrange it so that by November 1st new style, i.e. in a month upon receipt of this letter, whatever free money is found will be sent — but definitely to Paris, i.e. to a Parisian banker, as now the French monetary exchange rate is the most advantageous.

In other numerous letters, he mentioned gout and its effect on him as well. “I lay in bed like a slab for three weeks — and now I can barely crawl." He continued to be ill until November, all that time staying in Baden before the long-awaited trip to Paris, which he also mentions more than once, and which he has to constantly postpone due to illness.

By the end of October, according to Turgenev, the gout had almost passed, and he could already walk, albeit with difficulties, but by the beginning of November it returned again.

Thus Ivan Sergeyevich writes to Annenkov:

Live and learn, my dear friend P V. I had no idea that one could bring upon oneself a renewal of a gouty attack by fatigue — I walked carelessly while hunting (although I limped) on Friday — and since Saturday I have been lying motionless in bed again, having endured fierce torments, and only from tomorrow do I have hope to rise—with the help of two crutches. There it is, the fickle... old age! It will not yield to "youth"!

He had already sold his house in Baden-Baden to Pauline Viardot, his friend and to whom, as it is now commonly believed among biographers, he had romantic feelings.

My house here, which, by the grace of my uncle, was sold by me to Madame Viardot, has now been sold by her, with my consent of course, finally to the Moscow banker Achenbach and from November 1st passes into his possession. (The Viardot family, as you know, is moving to Paris, she is parting with Germany). I felt a little sorry for my nest... however, it is not for nothing that Tatar, nomadic blood flows in me: there is no sense of settledness—and any house is like a tent.

Turgenev was supposed to leave his residence by November 1st and depart for Paris to the Viardots, but the returning gout forced him to temporarily settle in their family villa in Baden, from where he writes to Annenkov on November 3rd:

As you can see from the inscription, I no longer live in my former house, which now presents an image of chaos: the new owner wants to redo everything there. Having parted with Baden, I will probably never see it again: "die schönen Tage von Aranjuez sind auch hier vorbei."

At this very time, Friedrich Nietzsche is in the same part of Germany, possibly geographically closer to Ivan Turgenev than ever before.

Unlike for Ivan Sergeyevich, the autumn of 1871 became a time of joyful meetings, creative inspiration, and important decisions for Nietzsche. On September 2nd, he writes to his mother about plans to go to Naumburg, and in a letter dated September 15th, he confirms his plans:

Here, my dear mother, follow the promised details about my departure.

On Wednesday, September 27th, in the evening, I leave Basel and therefore will be in Naumburg at about 5 o'clock in the afternoon on Thursday, together with Lisbeth, whom I will meet in Frankfurt. So you would have to seek out our Naumburg home a few days earlier, wouldn't you?

On the first day of October, the philosopher left quiet Basel, embarking on a journey that was to lead him to his native Naumburg via Wiesbaden, and consequently through Baden, where Turgenev was at that time.

In a letter to Deussen dated October 16th, Nietzsche describes the beginning of his journey thus:

I will receive my sister in Wiesbaden, and then we will travel together to Naumburg. Everything is arranged, and a change in our plans is impossible.

In Naumburg and Leipzig, he met with close friends - Rohde, von Gersdorff, Krug, and Pinder. These days, filled with conversations and merriment, deeply impressed the young philosopher. Later, in a letter to Erwin Rohde dated October 20th, Nietzsche nostalgically recalls:

Tomorrow I return to Basel, rising from the feast of my holiday joys like a sated reveller. I have never spent them so solemnly and lavishly, and I know what I owe to my friends. But even more to all the demons, to whom we want to bring a joint thank-offering in an hour next: whereby we want to brilliantly confirm the ideality of time and space once. Next Monday evening at 10 o'clock, each of us shall raise a glass with dark red wine and pour half of it into the black night, with the words χαίρετε δαίμονες, the other half he shall drink. Probatum est. Bless it Samiel! Uhu! — I am making the announcement to Gersdorff.

The culmination of this journey was the celebration of Nietzsche's birthday on October 15th. In the same letter to Rohde, the philosopher warmly describes this event:

I spent it under the friendly assistance of Rohde, v Gersdorff, Krug and Pinder, with an unusual solemnity. It was the last day of a reunion with the aforementioned friends: we spent the previous week in Leipzig, in blessed celebration of remembrance."

In the same month, a landmark event for Nietzsche's academic career occurs. In a letter to Deussen, he reports:

There I have handed over my work 'The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music' to a publisher.

On October 20th, after three weeks of travel, Nietzsche leaves hospitable Naumburg and returns to Basel to his usual life.

Looking at the railway route from Basel to Leipzig, one can conclude that on one of the days of his journey, Nietzsche could indeed have stopped in Baden-Baden, both on the way there and on the way back.

Monsieur A, driven by his passion for intellectual mediation, could not miss such an opportunity. Having somehow learned of Nietzsche's forthcoming journey, he immediately took up his pen. In his diary from the end of September 1871, he writes:

Sent a letter to N. today, urging him to visit Baden. Hinted at the presence of T. there and the possibility of a meeting. I hope my arguments prove convincing.

However, Monsieur A's enthusiasm encountered the practicality of the young philosopher. Although Nietzsche's direct response is not preserved in the diary, Monsieur A's subsequent entries testify that his proposal was politely but firmly declined. Not losing hope, our indefatigable mediator made another attempt.

Today I sent another letter, Mentioned T.'s ailment and that this might be the last opportunity for them to meet. Perhaps I somewhat exaggerated the colours, but does not a great goal justify a small measure of cunning?

Alas, these efforts of Monsieur A also proved futile. On October 5th, he notes bitterly in his diary:

N. passed through Baden without stopping… Is fate itself opposing this meeting? But I do not lose hope, for I am not some nihilist. Perhaps on his return journey...

After this, judging by the entries, Nietzsche ceased to respond to Monsieur A's letters. Despair begets madness, and madness begets desperate plans. An abnormal entry appears in Monsieur A's diary:

I have hired Monsieur S., a former actor now fallen on hard times, to meet N. in Naumburg, follow him everywhere and whisper to him just one word: “nihilism”, over and over again, in parks, in cafes, when he’s walking with his sister or his friends. I have instructed S. most meticulously. I am convinced that this will awaken in N. an interest in T.

He is to report to me daily.

However, Nietzsche, engrossed in reuniting with his family, meeting friends, and getting his work published, seemed not to notice his strange pursuer. Monsieur A writes with bitterness:

S. reports that N. absolutely does not react to his whisperings. Can he not hear the voice of fate? Or, perhaps, is S. not convincing enough?

No reaction followed. The answer was only silence. Monsieur A's despair reached its apogee. An entry appears in his diary that makes one doubt the author's sound mind:

October 15, 1871. Today is N.'s birthday, which he undoubtedly celebrates with friends in Leipzig. Nietzsche persistently ignores my letters. Well, if the mountain will not come to Mohammed... I have hired Monsieur R. to arrange a small incident on the tracks near Baden on the day of N.'s return to Basel. Nothing serious, just enough to force the train to stop. N. will have no choice but to disembark in Baden.

Later, Monsieur A would write:

The train stopped as planned. I rushed along the halted train, peering into every window. And there – oh, fate! – I saw him. Oh, those moustaches! But he... he simply looked through me, as if I were a ghost, a void. Has my face changed so much under the burden of these days? I feel like Sisyphus, whose stone has once again rolled down from the mountain top.

Perhaps, Monsieur A was a Sisyphus — one can only envy his persistence. Even this fiasco could not stop him. When Nietzsche returned to Basel, on one of the days Monsieur A made his last, most desperate attempt.

On that day, students who came to the lecture of the young professor of classical philology witnessed a strange and somewhat frightening spectacle. Nietzsche had just begun when the door of the auditorium burst open with a crash.

Two men, dressed in Russian fashion of the 1850s, burst into the room. One of them, with thick sideburns, in an elegant frock coat, clearly portrayed Pavel Petrovich Kirsanov. The second, in a shabby frock coat, with a carelessly tied neckerchief, apparently represented Yevgeny Bazarov.

"Bazarov" stepped forward and, ignoring the astonished Nietzsche, began his tirade:

—Formerly, in the recent past, we used to say that our officials take bribes, that we have neither roads, nor commerce, nor proper courts...

— Well, yes, yes, you are denouncers,—interrupted him “Kirsanov”.—I believe that's what it's called. With many of your denunciations I agree as well, but...

—And then we realised that to chatter, only to chatter about our sores is not worth the trouble, that it leads only to banality and doctrinairism; we saw that our clever men, so-called advanced people and reformers, are no good; that we are occupied with nonsense, talk rubbish about art, unconscious creativeness, parliamentarianism, trial by jury, and the deuce knows what all; when the question is of daily bread, when the grossest superstition is stifling us, when all our joint-stock companies burst simply from the lack of honest men, when the very liberation, which the government is busy upon, is hardly likely to be of advantage to us, because our peasant is glad to rob himself to get drunk at a pub.

—So,—interrupted “Kirsanov”,—so you are convinced of all this, and have decided to seriously undertake nothing yourself?

Nietzsche, momentarily frozen in surprise, quickly composed himself. He did not interrupt the "performance", but neither did he participate in it. Instead, he continued his lecture as if nothing unusual was happening, only occasionally raising his voice to drown out the actors' lines.

—And have decided to undertake nothing, — repeated Bazarov grimly.

—And only to scold?

—And to scold.

—And that is called nihilism?

—And that is called nihilism, — repeated Bazarov again, this time with peculiar insolence.

The students in the auditorium were bewildered. Some followed the unfolding scene with interest, others tried to concentrate on their professor's words. In the back rows, one could notice a pale middle-aged man with feverishly shining eyes, who watched the proceedings with agitation.

When the actors finished their act, Nietzsche paused only for a second to say:

—I thank the gentlemen for this... unexpected illustration to the topic of our lecture today - on the role of dialogue in ancient drama. And now let us return to Euripides...

After this, Monsieur A disappeared from the auditorium as suddenly as he had appeared, leaving behind only perplexity and a strange sense of unreality of what had happened.

Thus ended his diary as well. We know nothing more about the events of autumn 1871, only that autumn turned golden and gilded, the leaves fell, and winter began.