Greetings, bibliophiles!

Today, I’m very excited to bring you

, one of my favourite people on Substack.Andrei writes

, where he posts intimate memoir and personal essays. Reading Andrei’s stories and thoughtful essays, I have to remind myself that English is his second language.Here, Andrei delves into the book that began his writing journey - the spark that lit the flame of his writing passion. Enjoy!

—

It may be hard to believe given my choice of craft, but as a kid, I hated reading.

Actually, hate is too weak a word. I loathed it, despised it, and whenever I was forced to open a book the weight of my eyelids would increase tenfold, my head would droop forward like a snowdrop, and more often than not, I’d doze off.

Make no mistake, I tried to love books. I’m not somebody who gives up easily. But though I loved their beautiful covers, neither Heidi nor Robin Hood nor even Joseph Delaney’s The Last Apprentice novels, popular in Romania when I was in primary school, could hold my interest for more than a few pages.

Instead, I turned to more explosive forms of entertainment. I devoured comic books, video games, and animated series. I knew the origin stories of every major Marvel and DC character along with most of the minor ones, and could navigate their complicated web of relationships and timelines like I could the lines at the back of my own palms, which is to say, with my eyes closed. As for games, it was all action: God of War, Spider-Man (obviously), and Skyrim. Mortal Kombat: Armageddon, when I discovered it randomly in a supermarket, was a revelation, and hot on its heels came Tekken 5 and Street Fighter IV. Comics and games were full of punches, fantabulous (to borrow

’s phrase) superpowers, explosions, and COLOR! How could endless strings of black letters on white paper compete with that?Everything changed in twelfth grade, a year after I first met Mrs Samson. A slight lady, with a back so hunched it resembled a question mark, she was going to help me prepare for the law school admission exam. She was a teacher of Romanian language and literature, but our first year together, all we did was study and talk about grammar. That was, after all, what the exam was going to test. She was a very patient and understanding teacher (just the way I like them!), and between theory and exercises, we’d sometimes find ourselves discussing literature, by far her favourite subject.

If she could tell I didn’t share her passion, she never let it show. But from the start, I found myself intrigued by her discourse. The way Mrs Samson talked about books, as though she’d lived inside each one as she was reading it, as if every page she’d ever turned had left an indelible mark on her heart and soul, was completely unlike any other discussion on this topic I’d ever taken part in. My parents were readers, but it seemed to me they read almost from obligation, to themselves and to the world, to get through as many classic novels as they could before their time in this world was up. Mrs Samson read because she enjoyed it.

The following year, we began to study literature in earnest. That year, in addition to and before the law school admissions exam, I was going to take the baccalaureate, the exam every Romanian student is supposed to take after they finish high school, and one of the three subjects would be Romanian literature.

Again, I remembered the way I had studied literature until then—like following a recipe that never changed: read the book, then memorise a couple of literary critics’ opinions about the book, so you can write your own argumentative essay come exam time. Contrasting it to Mrs Samson’s approach, it felt like I’d just discovered magic was real.

What did she do that was so different? She had me read various fragments, short texts, and poems, and she really let me take my time with them. After, she’d let me discuss the text in earnest, what I liked, what I disliked, the way it had or hadn’t had an impact on me, and then she’d tell me her opinion. Invariably, there’d be things I had missed, a subtle insinuation, a layer of complexity, or a historical detail which, when pointed out, would turn my interpretation of the text on its head. There was so much depth to be found in even the shortest of paragraphs! I was completely enraptured.

I began to change my mind about reading. Maybe there was something to it after all. Yet, when I returned home after our lessons, I still booted up my gaming console and spent the better part of my afternoons bashing faces and blasting limbs.

One day, I found myself in a bookstore at the mall. I remember I was looking for a gift, though I could be mistaken. In any case, I guarantee I wasn’t there to buy a book. Yet this is what I did. The first book I’d ever bought for myself.

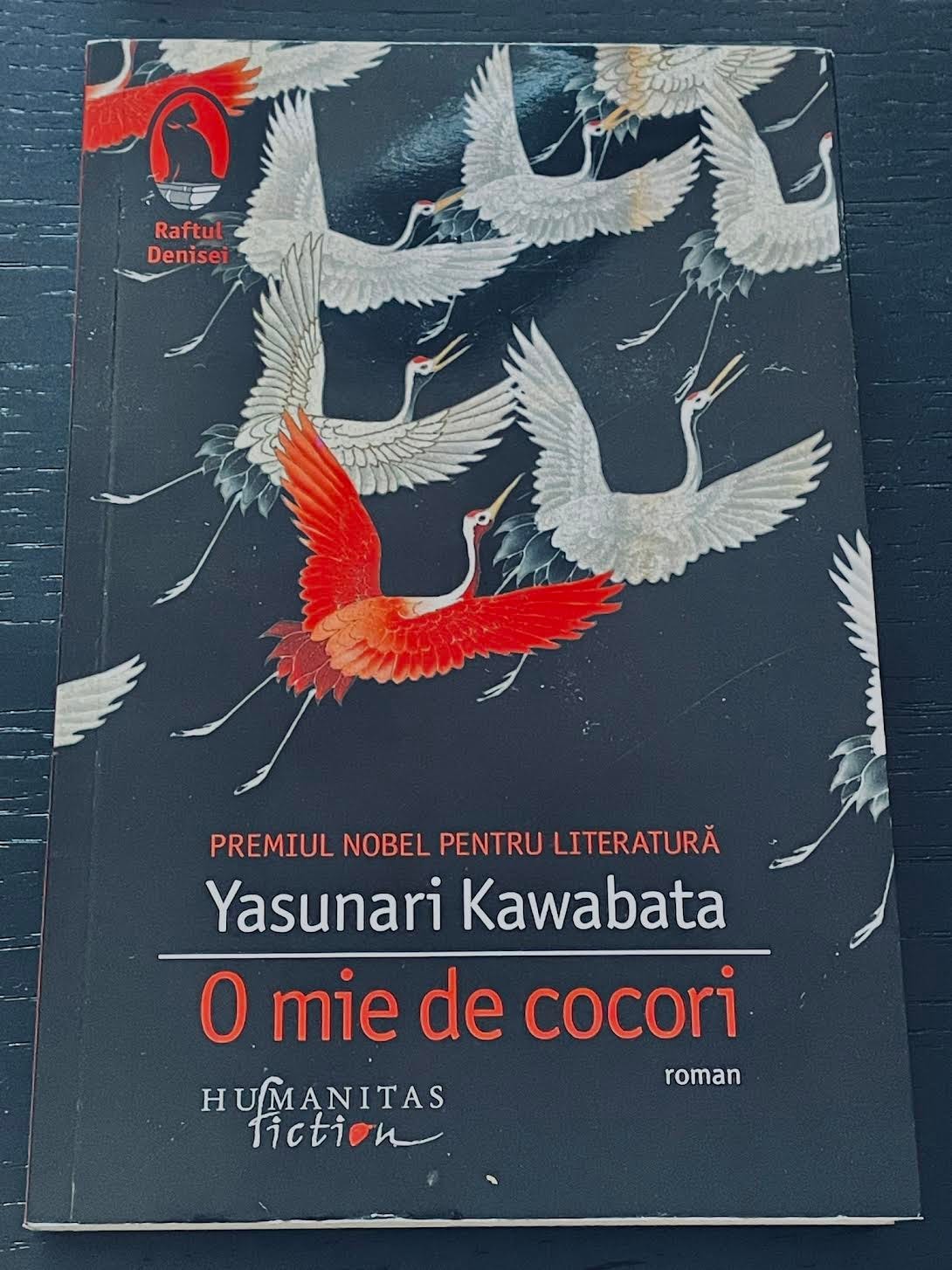

I won’t lie to you. It was the cover that first drew me in. I’ve asked Mikey to provide you with the cover to the Romanian version, which is not normally what happens here at

, just so you could see through my eyes at the time. And boy, what a cover, eh? Gorgeous, colourful, mysterious. To top it off, I was in my anime phase, so seeing a Japanese name on the cover made my nerd antennae go wild. I picked the book up and read the back blurb. Here’s what it said, in translation by yours truly:“A thousand cranes on a silk scarf: a symbol of happiness, a promise of a harmonious life. Thus begins the story of Kikuji, a man surrounded by multiple women: evanescent Miss Inamura, venomous Chikako, delicate Mrs Ōta—a mature and melancholy beauty—, and innocent Fumiko, the latter’s daughter. All their interactions are touched by the shadow of the tea ceremony, yet its subtle art and fragile porcelain utensils will neither be able to tame the characters’ feelings, nor to prevent their decay.”

I bought the book immediately. I mean, I didn’t even think about it. I rushed to the checkout counter in one breath and rummaged in my pockets for the money as the cashier rang up the book and the maybe-gift. It’s lucky I’d already gotten the latter, as I’d completely forgotten about it upon seeing the book.

It likely took me longer than necessary to read this book, given its length. But there were many passages that simply took my breath away, so that I was compelled to read them over and over, and the story and characterisation were accomplished with a brush so soft, it sometimes barely even left a mark. Like Mrs Samson, I wasn’t following the plot as much as I was living it. I was breathing, touching, tasting, feeling everything in tandem with the characters.

Rereading the book all these years later in preparation for this piece, I realize why Yasunari Kawabata won the Nobel prize in 1968. Thousand Cranes is timeless, and I enjoyed it now as much as I had then.

The book is a glorious exploration of decadence, of familial relationships tainted by morals and behaviours imposed from without, by death, and by secrets. The book is short, but filled with sensory detail: colors and smells are described with care and respect, as are objects. But I think the word that best describes this book is subtlety. Very few things are on the nose; most everything else is implied, hinted at, or merely presented as a possibility, and the author chose to limit even Kikuji’s knowledge of what was happening around him. Like him, the reader is bewildered by the actions of people dead and alive, and left to draw their own conclusions, if such a thing is even possible.

Simply put, this book changed my life. After Thousand Cranes, I became an avid reader. In the intervening eight-ish years, I read hundreds of books, of all sorts, though fiction will always have a special place in my heart, because of Thousand Cranes, and because of Mrs Samson.

After I passed the law school exam, I gifted her a copy of the book. She called me later to say she’d devoured it, and that was the final validation she gave me. I knew what good literature was now. And it was all thanks to her.

There’s so much more I want to say about her. Unfortunately, space, and your time, dear reader, are not limitless, and I’m afraid I’ve taken up too much of both. I will just say one more thing: had it not been for Mrs Samson, you would not be reading these words, nor anything else I’ve ever committed to paper. She was the spark that ignited it all.

Reminder that paid subscriptions to The Books That Made Us are 20% off for the next 30 days.

P.S. For more ways of getting your writing in front of new readers, consider becoming a paying subscriber today.

I never even heard of the book, but now I'll look for it to read it. Thank you

I enjoyed reading your essay. A lot.

I resonate with being bored by reading literature as a kid. I didn’t know I would be trying to write at all (not on a newsletter on Substack). In fact, Tekken 3 and 5 and Final Fantasy 6-10 were my go-to forms of entertainment. In 6th grade, I was absent for two days from school just to keep playing Tekken 3. It took me until senior high when friends introduced me to Eragon, Harry Potter (the books), and Lord of the Rings that I started taking an interest in reading literature. I then took an elective in local (Filipino) literature, which felt daunting at first, but it was worth it. Reading for fun became an important thing to learn.