The New New Seven Wonders of the World

A communiqué by Appraisal Bureau of Wonderful Monuments and Monumental Structures

Precious reader,

It helps to have positive thoughts about humanity sometimes. And although our trying times don’t often permit us to partake in the simple joys of empathy, compassion, and benevolence, at least we’re still pretty good at building amazing structures! And we, at the ABWMMS, are happy to remind you of that.

For instance, please consider the Seven Wonders of the World. This concept is pretty old. It is so old, in fact, that since almost all of the Wonders no longer exist (to be fair, we didn’t destroy all of them; earthquakes helped), people had to repurpose this name for other (similar) things and sheepishly rename the original to “Seven Wonders of the Ancient World”.

Unfortunately, the modern lists for the Seven Wonders of the World do not meet the high standard of the original. The USA Today one is highly inconsistent and includes Polar ice caps, the Great Migration of Serengeti, and “The Internet” (whatever that is). The maybe more appropriate one, compiled by a Swiss corporation called “New7Wonders Foundation” includes the Great Wall of China, Petra, and Colosseum, which are all suitable and definitely wondrous, but calling them “New Wonders of the World” is a bit of a stretch. The best list of all of these was compiled by the American Society of Civil Engineers and contains both age-appropriate and truly impressive feats of engineering, including the Golden Gate Bridge and the Channel Tunnel, but there is one crucial element lacking, and that is a connection to the past and to the original Wonders.

Which is why we decided to compile our own official list of the Seven Wonders of the Modern World. And in order to do that, we will go back to antiquity.

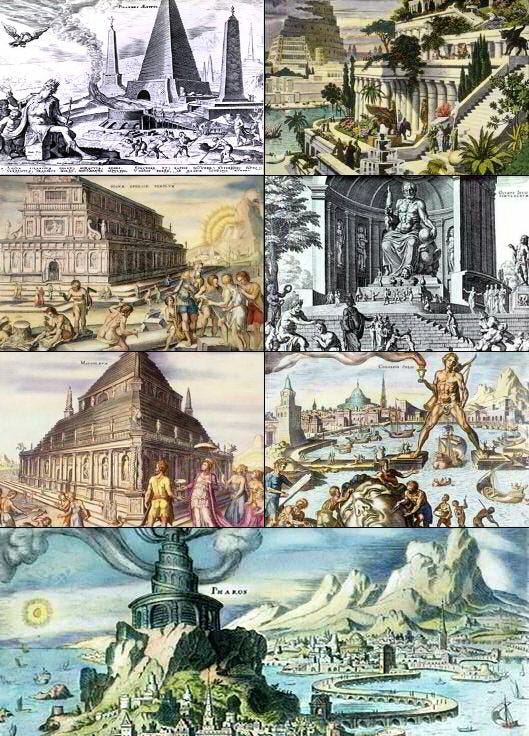

In order to compile such a list, we propose first to understand the principles of the original list and then apply those principles to the modern world. First of all, what are the original Wonders? They are, in the order of the construction date:

Great Pyramid of Giza (2584–2561 BC)

Hanging Gardens of Babylon (c. 600 BC)

Statue of Zeus at Olympia (435 BC)

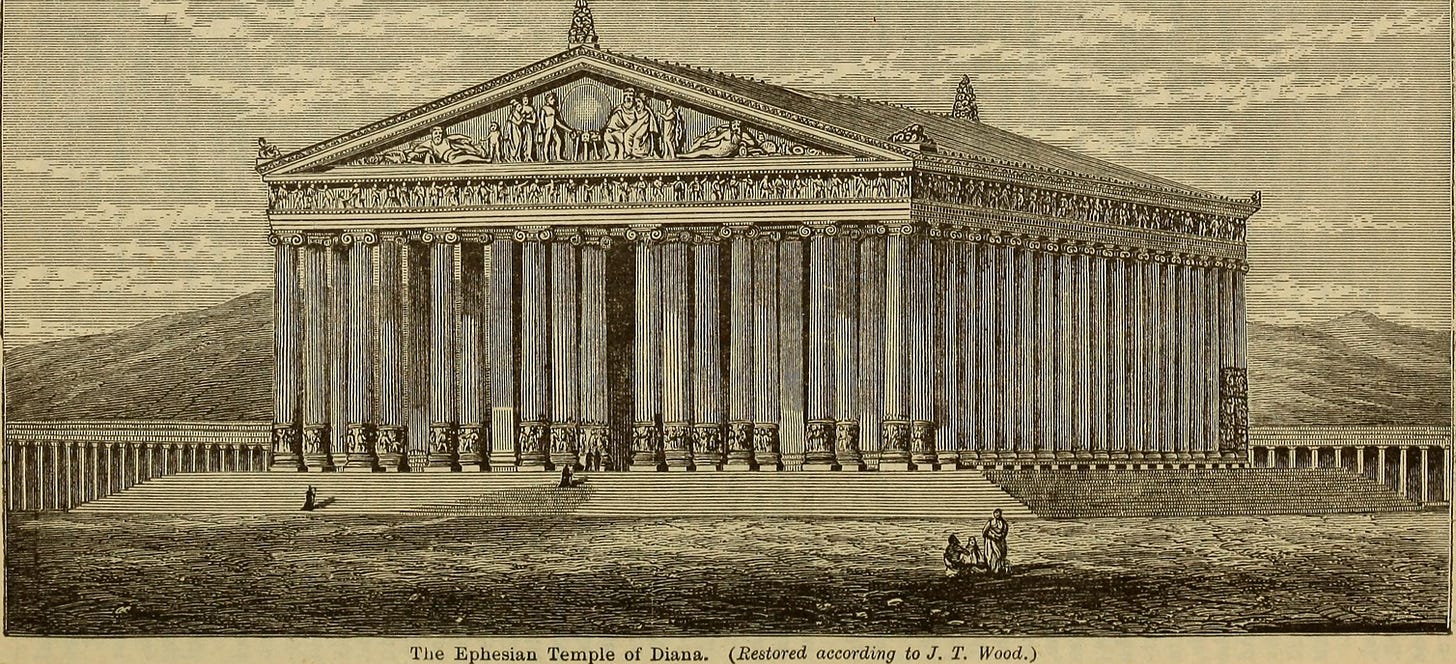

Temple of Artemis at Ephesus (c. 550 BC; rebuilt in 323 BC)

Mausoleum at Halicarnassus (351 BC)

Colossus of Rhodes (292–280 BC)

Lighthouse of Alexandria (c. 280 BC)

The original original list was probably compiled by Herodotus, but the first surviving list is found in the works of a Greek historian, Diodorus of Sicily. Instead of “wonders” the historian called them “θεάματα”, which roughly means “sights”, so one can say that this list is the OG sightseeing guidebook. That gives some justification for the “New7Wonders” list, but we can do better still. After all, they are not just sights. They are awe-inspiring achievements of humanity. All of the original Seven Wonders were incredible feats of ancient engineering. But in our jaded age, where incredible engineering is all around us, it doesn’t seem like enough. So, to qualify for the current list, in addition to an awe-inspiring structure, there also needs to be an awe-inspiring purpose.

In addition, we decided not just to slap seven spectacular structures together and then randomly number them. We believe, in order to be a true spiritual successor to the Wonders of the Ancient World, there must be parallels between the old and the new. And although a strict analogy between an ancient monument and a modern state-of-the-art construction can seem quite dubious, you will see, there are common themes. We can turn a sightseeing guidebook into a bridge over the river of time. So we will go one-by-one and try to find an analogue to the best of our knowledge and ability. We will also limit the search to the last 50 years to qualify for “modern” in the title.

Hanging Gardens of Babylon

Sometimes also known as the Hanging Gardens of Semiramis, after a legendary Assyrian queen.

By all accounts, these were a true marvel, not just in beauty but in engineering complexity and ingenuity. Intricate irrigation systems allowed for the construction of a a multi-level plant display, forming a square with a side of approximately 1.2 kilometers. It was first described by a Babylonian priest and historian, Berossus:

In this palace he erected very high walls, supported by stone pillars; and by planting what was called a pensile paradise, and replenishing it with all sorts of trees, he rendered the prospect an exact resemblance of a mountainous country.

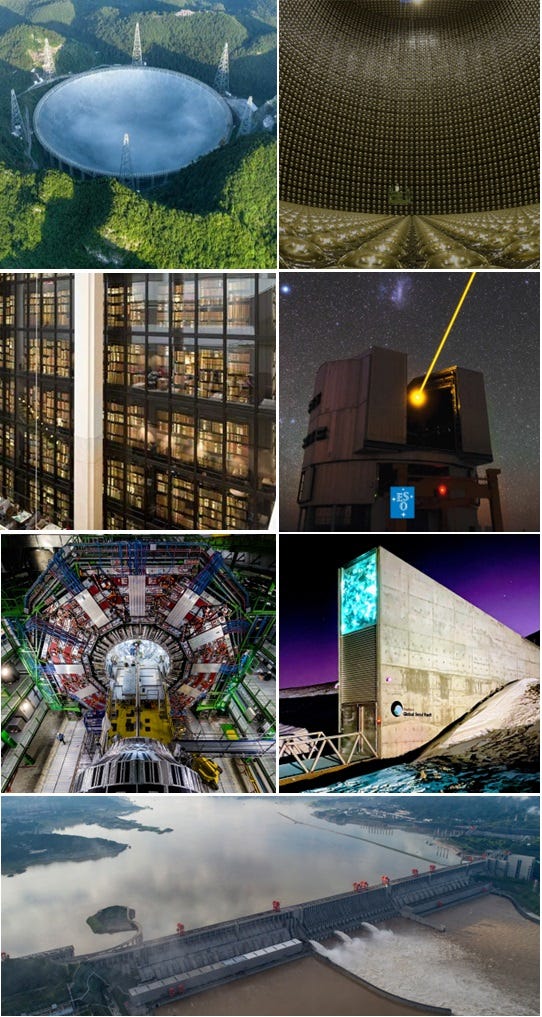

A modern counterpart could be, for example, a stunning botanical garden, like Kew Gardens or Rio de Janeiro Botanical Gardens, but we can dig a little deeper (dig? in a garden? get it?). One can interpret one of the ideas, one of the motifs, of such a structure as preservation. Berossus told us about “all sorts of trees”, but he was being poetic about it. However, in our times, we can allow ourselves to be quite literal about it and actually store all sorts of trees. The Svalbard Global Seed Vault stores around 1.7 million samples and serves as a backup to all other seed vaults in the world. It is also, appropriately, quite stunning to look at.

Colossus of Rhodes

The Colossus, a huge statue of the Greek god Helios, was about 33 meters high, approximately the size of the Statue of Liberty. Its architect, Chares of Lindos, according to one source, commited suicide when somebody pointed out to him a small flaw in the construction. Drama queen. The Collossus presumably stood at the entrance of the harbor of Rhodes, although there is no firm scientific (or even mathematical) basis for that.

Relevant Shakespeare’s text is quite nice, though:

Why man, he doth bestride the narrow world Like a Colossus, and we petty men Walk under his huge legs and peep about To find ourselves dishonourable graves.

To find a modern counterpart, we must consider the god Helios. He was a greek god of the Sun. To us, the Sun is somewhat less enigmatic than it was to the ancients, but we still in many ways worship light, and so this will be our keyword. And one of the ways we worship it is, of course, to use it for scientific discovery. So for this Modern Wonder of the World, we nominate the world’s largest optical telescope, aptly named The Extremely Large Telescope in Cerro Armazones, Chile. Since it is still under construction (ETA 2027), until then we temporarily grant the title to no less aptly named The Very Large Telescope in Cerro Paranal, Chile. Both of them were built to see as far as possible into the vastness of the universe and uncover its secrets.

We also encourage everyone to watch Tom Scott’s brilliant video on the VLT and the ELT. One can really feel the scope of these structures and appreciate the precision and intricacy of their construction. An awe-inspiring structure with an awe-inspiring purpose.

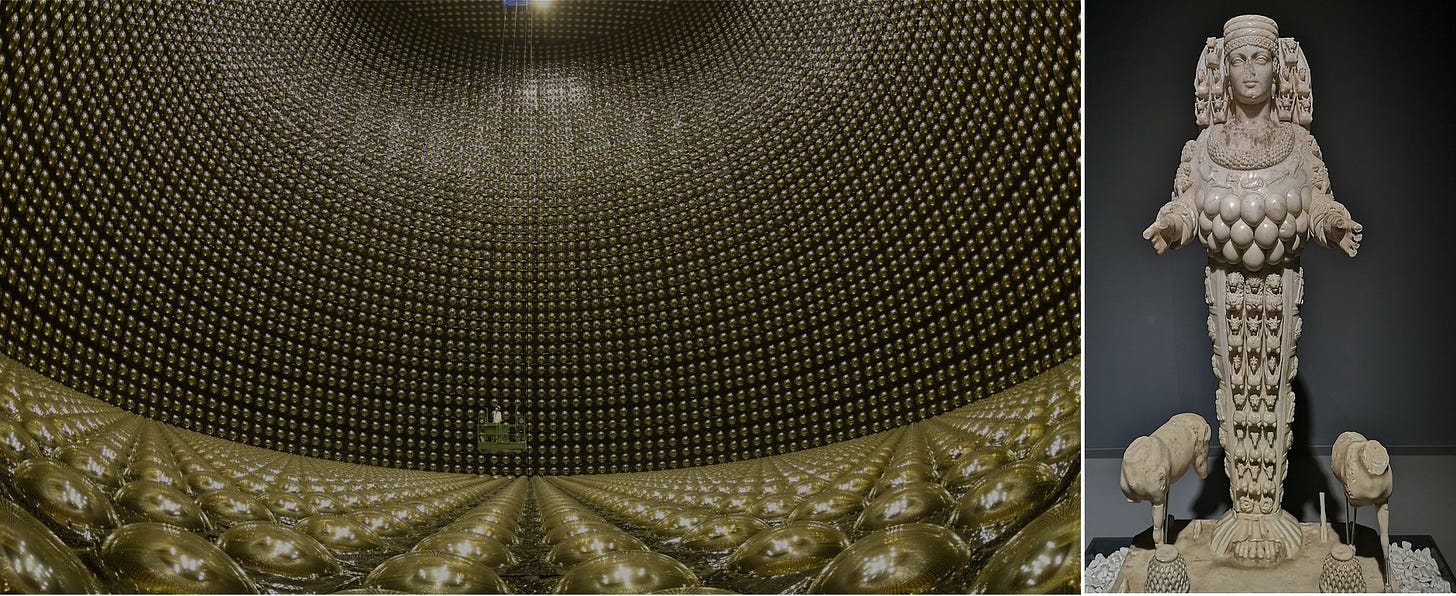

Statue of Zeus at Olympia

The Statue of Zeus, constructed by a famous Greek sculptor, Phidias, was about 12.5 meters high, which is slightly more than two Michelangelo’s Davids and one Michelangelo standing on top of each other. That’s not that tall, so it would be fair to assume that the awe-inspiring part is the fact that the statue is reported to be chryselephantine, i.e., made from gold and ivory.

Roman historian Suetonius wrote that emperor Caligula ordered for the statue to be “brought from Greece, in order to remove [its] head and put his own in [its] place." The emperor was assassinated before that could happen, and it is reported that the statue "suddenly uttered such a peal of laughter that the scaffolding collapsed and the workmen took to their heels”. The bitter irony here is that the statue perished in a fire some 350 years later; it is not inconceivable that if the head-swapping took place, we would still be able to see it in Rome. Zeus can laugh, but Momus laughs louder still.

For the modern analogue, we all know that Zeus was a god of thunder and lightning, but maybe more generally (and as 12 meters of gold and ivory subtly hint at), he was the king of the gods, and his motif, in myth or in sculpture, is power. In modern times, power is expressed not in gold or ivory, and not even in thunderbolts, but in megawatts. As much as we wanted to include the world’s biggest nuclear power plant (Kashiwazaki-Kariwa Nuclear Power Plant in Japan), it (along with most other things) is dwarfed by the Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze River, which generates 30% more power than the next largest power plant, or approximately what the three largest nuclear power plants generate together. It is also breathtaking.

Lighthouse of Alexandria

The Lighthouse of Alexandria, also known as the Pharos Lighthouse for the small island it was actually on, was constructed during the reign of Egyptian monarch Ptolemy II, presumably by an architect named Sostratus. A Roman historian, Lucian, writes about the construction:

After he [Sostratus] had built the work, he wrote his name on the masonry inside, covered it with gypsum, and having hidden it inscribed the name of the reigning king. He knew, as actually happened, that in a very short time the letters would fall away with the plaster and there would be revealed: 'Sostratus of Cnidos, the son of Dexiphanes, to the Divine Saviours, for the sake of them that sail at sea.'

Well played, Sostratus. Unlike the previous Wonders, we actually have a fairly accurate description of the lighthouse by an Arab traveller, Abou Haggag Youssef Ibn Mohammed el-Balawi el-Andaloussi, decent schemes, and even a 3D projection. We somehow still prefer these:

It is also fairly easy to propose a modern analogy to a lighthouse. I think the establishing motif here should be communication, a signal; after all, that is what the lighthouses are for. That, again, screams telescope—not an optical, but a radio one—capable of not just observing but sending a message to anyone ready to listen. RATAN-600 is a close runner-up here, but for the sheer visual incredibility, the Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope (FAST), located in Guizhou, China, takes the cake.

Mausoleum at Halicarnassus

Usually, when we hear the word “mausoleum”, it is either preceded or followed by the name of the person buried there, like Lenin’s Mausoleum or the Mausoleum of Hadrian. Not in this case. Mausoleum at Halicarnassus is a tomb of an Achaemenid satrap, Mausolus, who, in fact, gave his name to the whole structure type. This is theMausoleum, the Platonian idea of a Mausoleum. It was also a very impressive structure.

The modern equivalent, however, is a little tricky; after all, it is just a tomb of a dude. So we had to delve a bit deeper into the bogs of history to finally understand this particular dude, and therefore, the motif of this Wonder. You see, Mausolus took his legacy very seriously. Together with his sister-wife Artemisia (skipped right past this one, didn’t we?) they completely rebuilt the city of Halicarnassus, inviting very popular Greek architects and generally bringing the age of hellenisation to the Achaemenid Empire. The Mausoleum was his ultimate attempt to remain in the memory of humanity. And an amazingly successful one, since we invoke his name every time we bury yet another important dude. Mausolus literally built a mausoleum in our language, and this one survived all the earthquakes. So the motif of this Wonder is, again, preservation, but not of lifeforms. It is the preservation of words and names, or, simply put, memory.

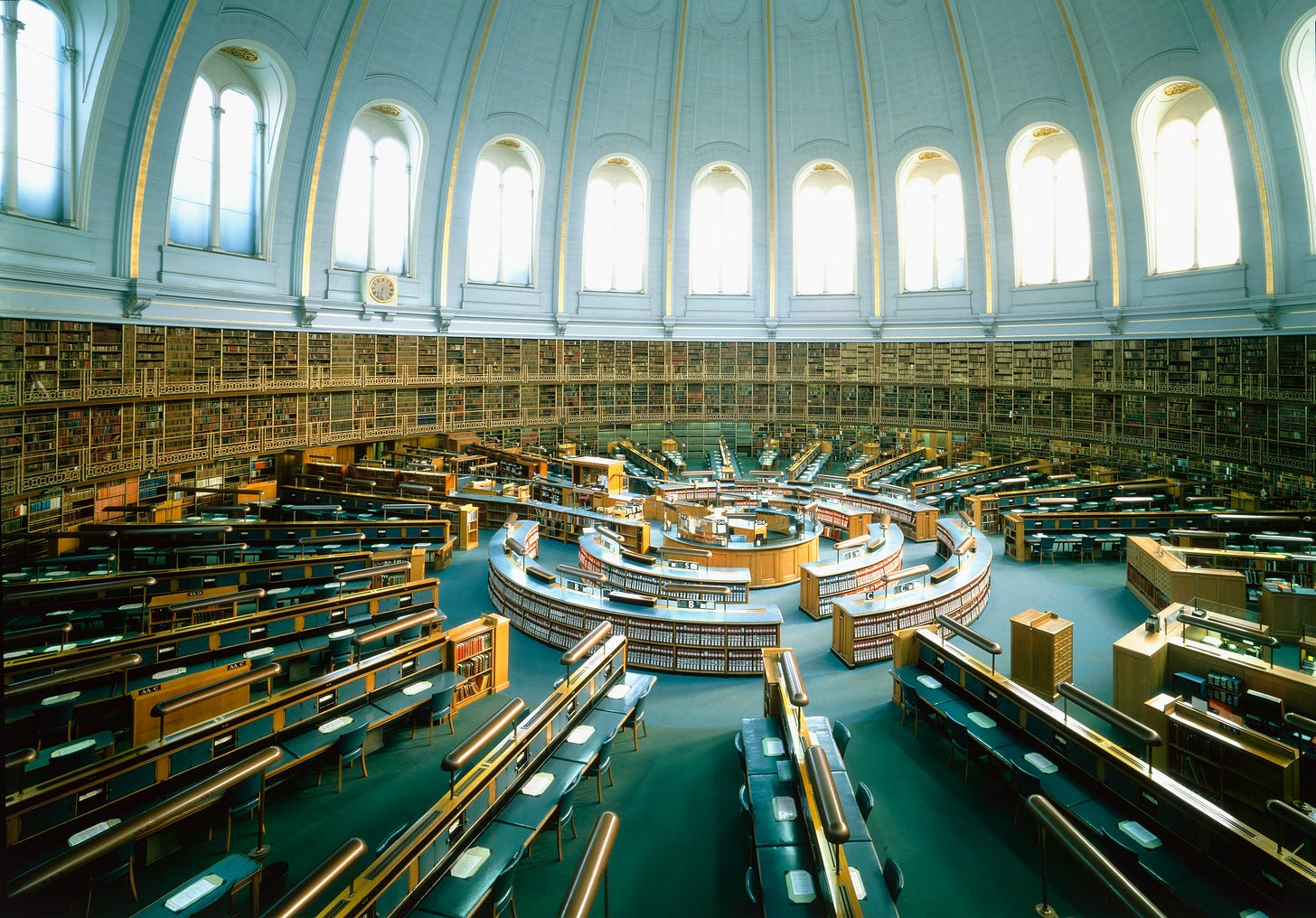

There is no surprise then, that the analogue of the Mausoleum is a modern symbol of memory. If Wikipedia were a real-life object, it would definitely qualify, but for now we will choose the biggest library in the world, the British Library (both the main complex and the Round Reading Room in the British Museum). It only barely overcame the Library of Congress, which deserves an honorable mention here. It is also a feat of the most intricate engineering, if you consider the care and different climate conditions all these ~200 million books require to be meticulously preserved. One can think that it’s not very awe-inspiring, but you know what? It’s absolutely magnificent:

Temple of Artemis at Ephesus

The Temple of Artemis had a troubled history. It was constructed, then destroyed by a flood, then reconstructed, and then destroyed by an arsonist. This second version specifically is considered to be the Wonder of the Ancient World, and by eyewitness accounts, it was something special. The Greek historian, Antipater of Sidon, wrote:

I have set eyes on the wall of lofty Babylon on which is a road for chariots, and the statue of Zeus by the Alpheus, and the hanging gardens, and the colossus of the Sun, and the huge labour of the high pyramids, and the vast tomb of Mausolus; but when I saw the house of Artemis that mounted to the clouds, those other marvels lost their brilliancy, and I said, "Lo, apart from Olympus, the Sun never looked on aught so grand".

The Temple’s destruction was brought about by a man named Herostratus, with a very specific reason: to get famous for it. Evidently, like Mausolus, he succeeded, enriching our language with the term “herostratic fame”. One can only ponder the two different approaches to fame-seeking and draw unpleasant parallels with the modern world. We can also quote a piece by Russian writer and comedienne Nadezhda Teffi from her satirical retelling of ancient history:

The Madman Herostratus

The city of Ephesus was renowned for its temple of the goddess Artemis. Herostratus set fire to this temple in order to glorify his name. However, when the Greeks learned of the purpose behind this heinous crime, they decided to condemn the name of the criminal to oblivion as punishment.

For this purpose, special heralds were hired, who, for many decades, traveled throughout Greece and proclaimed the following decree: "Do not dare to remember the name of the madman Herostratus, who, out of ambition, burned the temple of the goddess Artemis."

The Greeks knew this decree so well that you could wake any of them up in the middle of the night and ask, "Whose name must you forget?" And without hesitation, they would answer, "The madman Herostratus."

Thus, the ambitious criminal was justly punished.

Finding the modern equivalent of this Wonder, however, is not an easy task. One could remember that Artemis is a goddess of, among other things, hunting, wild nature, childbirth, and chastity. A mixed portfolio, to be sure. However, one idea comes to mind, and that is discovery, as in scientific discovery. There is an element of hunt in it and an element of childbirth, and a lot of it concerns nature. (And please spare us the “scientists are virgins” jokes.)

So what would be a good representation of the modern idea of scientific discovery, such that it would also include an awe-inspiring construction? We had telescopes that see galaxies, so this time we would focus on the tiniest. Our proposition is a neutrino detector: they are huge, look absolutely alien, and are quite unlike anything you ever saw. The IceCube neutrino detector would be a great candidate. But even more spectacular ones are the Super Kamiokande (take the 360° tour on the website!) and the soon-activated Hyper Kamiokande in Japan. These structures allow us to hunt the miniscule, the most inperceptible particles in the universe, and give birth to abundant scientific theories. If you’re still not convinced, there is also a certain visual rhyme. Yes, the boobingtons (scientific term!).

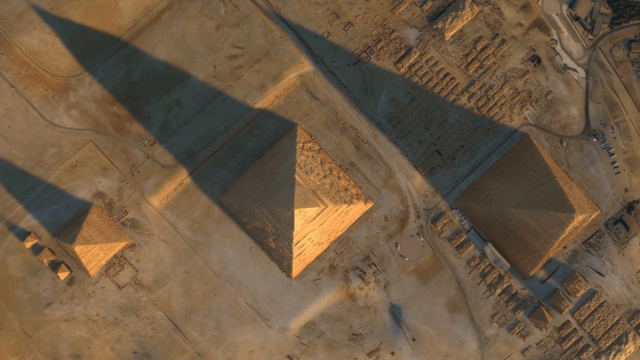

The Great Pyramid of Giza

The Great Pyramid was built almost two millennia before the rest of the Wonders, and survived at least half a millennium longer. (Although some say that they are still there only because they were too heavy to be taken to the British Museum.) This is the only original Wonder that we can see a photo of. Hell, this is the only original Wonder that we can take a photo of! Or a drone footage.

And of course, the only motif there can be with such a timeless structure is time itself. As we still struggle to comprehend this elusive and all-permeating concept, sometimes it’s worth remembering that the ancient Egyptians also had some ideas about it. Theirs were expressed in stone blocks, limestone, clay, and water, and it’s still fascinating to me what they managed to build with such simple starting materials.

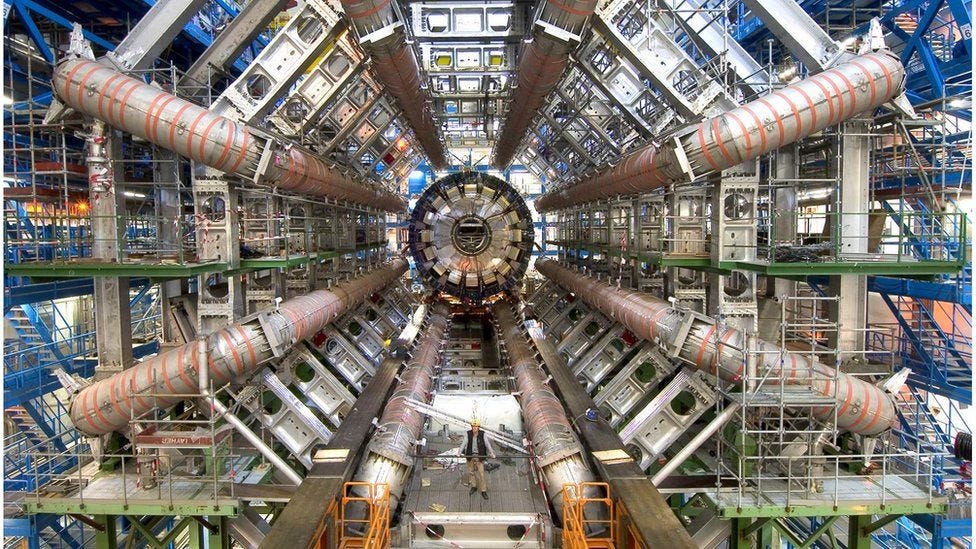

Our ideas about time are expressed in superconducting magnets. Of course, no list of the Wonders of the Modern World can ever be complete without the Large Hadron Collider. The scale of this structure speaks for itself, but the purpose might not be obvious. In a way, it is the exact opposite of a pyramid. In the pyramid, everything lies very still, being very dead. In the LHC, everything moves at near-light speeds and collides with each other, giving life to new things.

The List

So there we are. As we said in the beginning, we might be prone to war and stupidity, but we still can build! Specifically, the Seven Wonders of the Modern World:

The British Library (1973)

Super Kamiokande (1996), to be replaced by Hyper Kamiokande (2027)

Very Large Telescope (1998), to be replaced by Extremely Large Telescope (2027)

Three Gorges Dam (2003)

Svalbard Global Seed Vault (2008)

Large Hadron Collider (2010)

Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope (2016)

Thank you for your attention. Incidentally, if you are a Wikipedia editor, you know what to do!

What a wondrous job you accomplished to show us all the wonders of the world! Thank you1

I am most moved by the seed vault. A beautiful structure and a magnificent idea: attempt to aid the future by saving life itself.