Greetings, bookworms.

Today, I’m very excited to bring you an excellent piece from the brilliant

.Sarah writes two newsletters,

— where she mentors writers on how to produce their best work on Substack and use it to further their writing careers — and where she shares her story of recovery from twenty-five years of serious mental illness and offers readers the latest research, tips, and expert guidance on recovery.—

Listen to Sarah read her essay:

It was 1997. My boyfriend, Chris, went out to the vegetable garden in our backyard and returned with two armfuls of freshly picked yellow squash.

“They’re going to go bad,” he said with a smile and set to work in the kitchen.

The apartment we shared was perfect: a two-bedroom in a two-flat in a not-quite-gentrified neighborhood in Chicago. No one lived in the apartment upstairs, so it was like having our own little house. The wood floors were beaten up, and the shabby windows drafted frigid air in the winters, but it had a big kitchen, a dining room, and what seemed to us like a huge backyard.

It was Chris’s idea to grow vegetables. The garden bordered an abandoned lot on one side and an alley on the other. Only a barbwire fence protected the garden from the cars that sped past, kicking up gravel and dirt and trash. We were so proud of it. In part, it was a response to the limited options for groceries. The local grocery store sold aisles and aisles of canned food, ten-pound portions of frozen chuck roast, and wilting iceberg lettuce that was often out of stock. We answered with plentiful harvests of zucchini, thyme, and cilantro. Too much basil and too many tomatoes meant we ate balsamic-tomato-basil salads for days in a row. Chicago had its first Whole Foods but compared to our homegrown peppers, theirs looked almost artificial in the glare of the store’s fluorescent lights.

I mention the garden and food because I’d struggled with and had sort of overcome a long battle with what the doctors and mental health professionals I saw categorized as anorexia. It started at age twelve. I don’t need to tell you how it went. There are enough eating disorder memoirs and movies and TV shows and social media accounts and websites that you already know. Basically, it started small, later crescendoing into a hospitalization program, finally becoming too tiresome and difficult to maintain. It just sort of withered away, leaving me with the standard food and body obsessions and strain so many American women feel about food and their bodies.

That’s not to say I was well; I wasn’t. The emotions of fear, anxiety, and sadness were at the core of what was named anorexia and weren’t dealt with. Treatment back then was ineffectual. They pretty much blamed my parents, which helped not at all, and considered me hopeless, telling my parents that I’d always “be anorexic” (as if it was me) and likely die of it. My care was primarily triage: Get her eating. My emotions, particularly how to manage depression, never came into it.

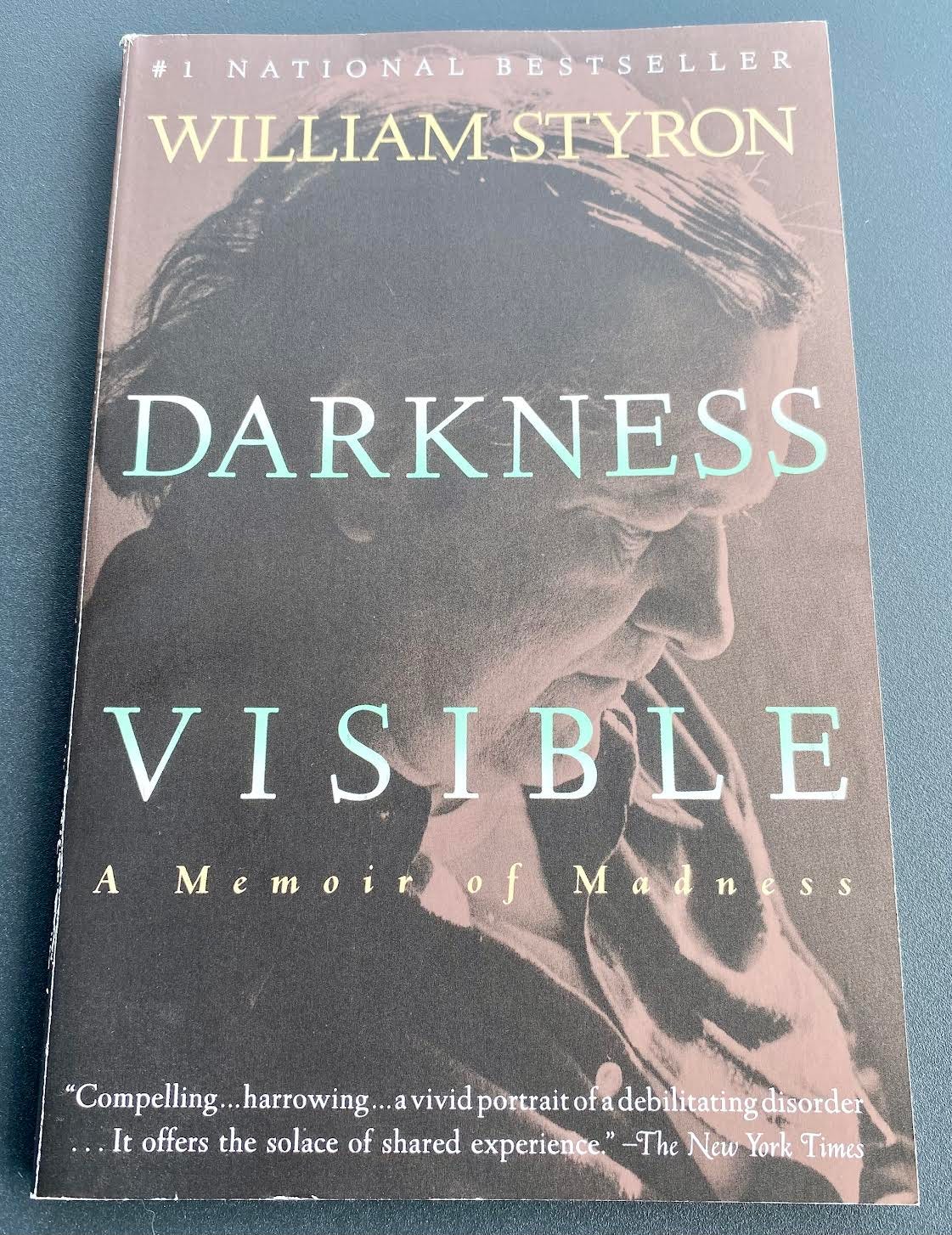

One day, while Chris worked the lunch shift at the restaurant where he waited tables, I went to our bookshelf. William Styron’s Darkness Visible: A Memoir of Madness wasn’t a book I remembered buying. It must have belonged to Chris—or maybe I had bought it. I didn’t know. The spine was barely creased and the pages crisp.

The cover was a deep purple image of a shadowing figure. The words unsettled me: A Memoir of Madness.

Styron wasn’t a writer I knew much about. At twenty-five, I had none of the knowledge I have now about literature. After an MFA in creative writing and a Ph.D. in English, I know too much about authors and books to the point that biographical data and literary criticism often get in the way of my ability to simply enjoy them. But back then, Styron was just a writer. Darkness Visible was just a book.

If you don’t know Styron, he was one of the most revered writers of his day. His books were once legendary: Lie Down in Darkness (1951), which he wrote at the tender age of twenty-six to much acclaim; The Confessions of Nat Turner (1967), which spurred much controversy but also earned him a Pulitzer; and Sophie’s Choice (1979), a harrowing story of a woman in Nazi Germany, which won the National Book Award and was turned into an Academy-Award-winning film starring Meryl Streep (highly recommended). He was also the classic alcoholic writer.

When Styron’s memoir Darkness Visible was published in 1990, it rocked the literary world—and perhaps the whole country. Depression was still stigmatized to the point of condemnation. Suicidality either wasn’t talked about or denounced. Men, especially, weren’t supposed to suffer from either. Ever. Styron wrote it to change all this.

The day I read it I sat in our backyard in the sun. The tomato plants were producing round, succulent fruits. The basil and cilantro plants were plentiful to the point of being out of control.

I finished most of Darkness Visible in one sitting, getting sunburned in the process. My legs felt shaky as I stood. It was as if Styron was speaking directly to me. His depression didn’t make him feel heavy and sleep all day. He had what his doctors called atypical depression: fine in the morning—buoyant, even—only to be crushed by gloom and dread and anxiety in the late afternoon. Almost exactly how I felt. I wanted to ask if he had a stomachache, too.

Believe it or not, Styron gave me my first understanding of depression. It was the beginning of the “age of depression,” but I didn’t know that. The antidepressant Prozac had been around for nearly a decade and was grossing the pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly $2 billion annually. Elizabeth Wurtzel’s depression memoir Prozac Nation was a bestseller. (This must also be hard for you to believe, given our current culture where diagnoses are used to define anything having to do with mental or emotional pain.)

Styron’s book scared me. He referred to atypical depression as a “mood disorder”—which sounded serious—and defined it as a biochemical malfunction that resulted from “systemic stress” amid “neurotransmitters of the brain” that caused the depletion of serotonin.

It would turn out that Styron was wrong on all counts. The chemical imbalance theory has never been true. In the 1980s and 1990s, it got tossed around by biopsychiatrists and embraced by pharmaceutical companies so convincingly that 80 percent of the American public still believe depression and most psychiatric disorders are caused by a “chemical imbalance” even though they’re not. You can read more about this in my memoir Pathological: The True Story of Six Misdiagnoses—HarperCollins 2022.

Even if he hadn’t gotten the science of depression wrong (not his fault—that was the psychiatric mythology of the time), it still would have scared me. It’s penetrating when a book speaks to the darkest parts of us. (No pun intended.)

But Styron ends on a note I wish I’d read more carefully. Psychiatry has convinced most of us that every psychiatric diagnosis is lifelong. They’re not. You can read more about this in my memoir Cured, which I’m serializing right here on Substack (!). Styron knew and tried to tell us that diagnoses aren’t permanent, and neither are psychic suffering and painful feelings. The penultimate chapter begins with this, which I’ll leave you with too:

“By far the great majority of the people who go through even the severest depression survive it, and live ever afterward at least as happily as their unafflicted counterparts. Save for the awfulness of certain memories it leaves, acute depression inflicts few permanent wounds. There is a Sisyphean torment in the fact that a great number—as many as half—of those who are devastated once will be struck again; depression has the habit of recurrence. But most victims live through even these relapses, often coping better because they have become psychologically tuned by past experience to deal with the ogre. It is of great importance that those who are suffering a siege, perhaps for the first time, be told—be convinced, rather—that the illness will run its course and that they will pull through.”

Sarah Fay’s journalistic memoir Pathological: The True Story of Six Misdiagnoses (HarperCollins) was an Apple Best Books pick, hailed in The New York Times as a “fiery manifesto of a memoir,” and named by Parade Magazine as one of the sixteen best mental health memoirs to read. Her new memoir Cured is being serialized on Substack for free through 2023. She writes for many publications, including The New York Times, The Atlantic, Time, and The Paris Review, where she was an advisory editor. She’s currently on the creative writing faculty at Northwestern University and runs Writers at Work, where she helps writers master the art and business of being on Substack.

P.S. If you’d like to write for The Books That Made Us, please see here.

Great post.

This is the first time, outside of my coursework in neuroscience, that I've encountered someone questioning the chemical imbalance hypothesis. Despite a complete lack of evidence, the field of psychology mostly remains split on it. As many psychologists believe it as disbelieve it (this was true, at least, fifteen years ago - no telling how the numbers split now).

One thing I wish people understood about depression and medication is that it takes roughly 6-18 months to figure out someone's medication and dose. Interestingly, even severe, lifethreatening depression typically resolves itself in 6-18 months. This resolution can happen even without external intervention. And so it's worth questioning, as someone in the bouts of depression, if you're feeling better because you and your doctor figured out your medication or because you simply feel better.

The fact that most medication that deals with mood disorders is addictive complicates this further, since one of the primarily side effects of withdrawal is depression. Thus and so, medicine meant to help us through a temporary difficult patch in life can become a lifelong dependence.

That's not to say that medication has no place in treatment, but that sometimes the cure is simply time and growing resilience.

This was a great post. It also made me think of this- as a reader, I tend to think what I read in a book as somehow verified or true. But, often, it’s just what is known or believed at that time or even just a point of view. It speaks to the ephemeral side of book content, something that I don’t hear about as often.