Greetings, fellow fiction-lovers!

Today, I’m very excited to bring you

.In her newsletter, the aptly named

, Robin writes multi-layered stories about people whose destinies are not determined solely by their sexual orientation or gender identity.Today, Robin shares with us her third story to feature here on The Books That Made Us. To a child, life can seem like an all-or-nothing prospect. Things and black and white; shades of grey are confusing. And toys are as real as people. Enjoy!

—

His name was Pandaboo. Somewhere I still have an old black-and-white photo of myself, a two-year-old girl whose dark hair is tied with ribbons so there are two tufts sticking out from either side of her head. I’m held tenderly by my father, hoisted up so our faces are on the same level, and in my arms is Pandaboo.

His arms are black and furry, the undersides of his paws finished with pads of white felt. His chest is white, his back is black, and his face is constructed just like a real panda. He has golden glass eyes nestled in small patches of black fur. In the center of the gold are black pupils with tiny black lines round the centers like dark rays. Oh, and his head swivels completely around. It didn’t occur to me until I was much older to wonder about this swivel feature. As a child, I found it fascinating.

Pandaboo was my favorite toy for the next two years. Maybe longer, but this story is about what happened when I was four. Just like in The Velveteen Rabbit (Margery Williams), Pandaboo showed signs of a child’s loving attentions. His little black ears, stuck high on his head, were floppier than when he’d been new, and worn around the edges. The fur on his chest wasn’t fluffy any longer, and not really very white. The condition of his face bore witness to how many kisses he had received. In short, he was beginning to look mistreated. And I was his tormentor.

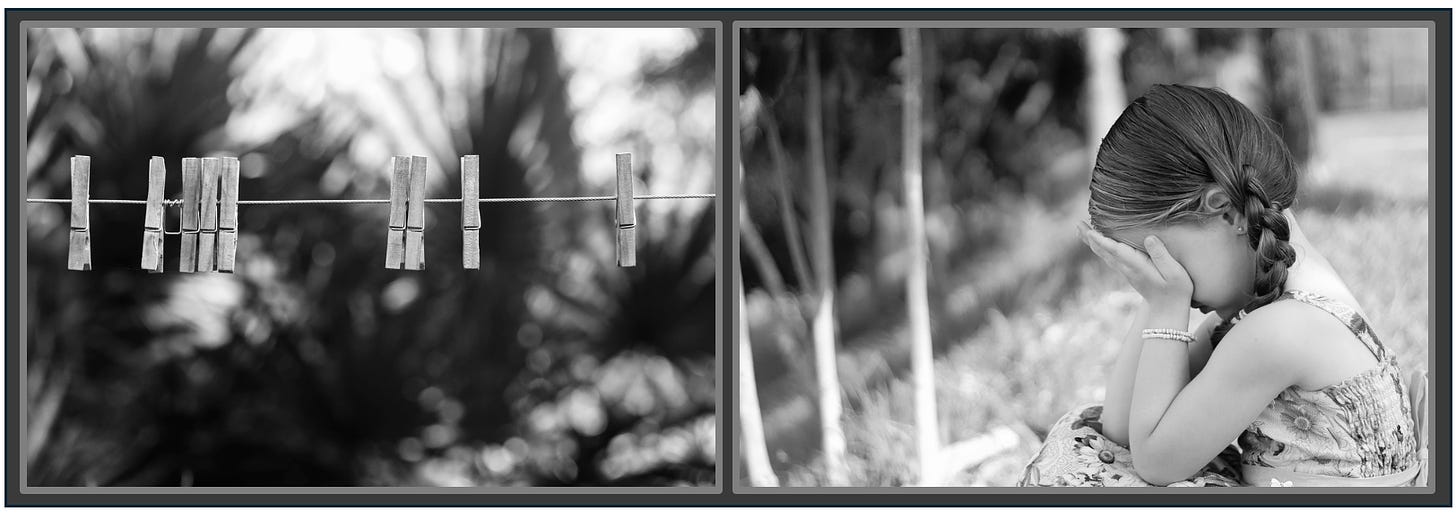

My family lived in a brick house, ranch style. The driveway led up beside the house, at which point it was shielded from the weather by a roof that continued across to cover a dark, utilitarian room with a concrete floor. In there was a clothes washer and a large sink—more of a tub, really. My memory is that the sink was a silvery color, and I suspect it was zinc. The faucets were large, and the spout formed what looked to my child’s eyes like a massive curve. There was no clothes dryer. Instead, in the back yard were metal posts that served as supports for the clothes line, wooden spring pins left here and there on the rope. A canvas bag, hung at one end of the rope, held more pins.

I chose a lovely summer day for my task. I was going to make Pandaboo like new again. Wash him clean. Remove the evidence of what I’d done to him. So I guess I was also trying to redeem myself.

Hugging the toy bear to my chest, I made my way into the dark laundry room. My mother was a stay-at-home mom, but at that moment I didn’t know where she was. At first it seemed my task was to be thwarted; I couldn’t reach into the sink. An up-turned pail solved the problem, and I set to work. Plug securely in the drain, laundry soap at hand, I ran water into the silvery tub and sloshed rather too much soap into it. When it was deep enough, I took one last look at grubby Pandaboo, soiled with the sin of my adoration.

“You’ll be so clean!” I assured him. And I plunged him in.

Swish, he went around the tub. I pressed down as well as I could to get the soap inside as well as outside, to be sure he was truly clean. I rubbed his face with the soapy water. I squeezed his paws.

“Robin, what are you doing?” My mother’s voice startled me, and the tone made it clear she was not happy with me.

I think my voice shook as I replied, “Washing Pandaboo.”

I don’t recall what she said after that, but I knew that somehow this was a bad thing I’d done. My mother lifted me off the pail I stood on and drained the tub. She ran cold water and did horrible things to Pandaboo, which I now know was to get as much soap out of him as possible. She wrapped him in a towel and leaned on him, hard. I knew she was hurting him.

I think I began to cry. I know I wanted to. But the worst was yet to come.

As I followed my mother into the back yard, I wanted desperately to wrest him away from her. If I had known what she was going to do, I might have tried something. Anything. Because what she did was hang Pandaboo on the clothesline, wooden pins pinching his sweet little ears to hold him, dangling and helpless. Without a word, she went back into the house.

He was in pain! Agony! And it was because of me.

I’m sure I cried. I think I wailed, unable to reach high enough to rescue Pandaboo, my crucified bear.

P.S. If you’d like to see your fiction hosted on The Books That Made Us, please see here.

Thank you much for featuring my work. And yes, Pandaboo is as real to me today as ever he was. And in my mind's eye, he's pristine.

Very thought provoking. Thank you