Greetings, my fellow bibliophiles!

Today, I’m very excited to bring you

.TaraShea writes

, where she gives out multi-genre creative writing prompts, craft glow-ups, and love, on a regular basis.Here, TaraShea shares with us a wonderful essay on the parallels between her and the title character of the book that made her — Mathilda. Enjoy!

—

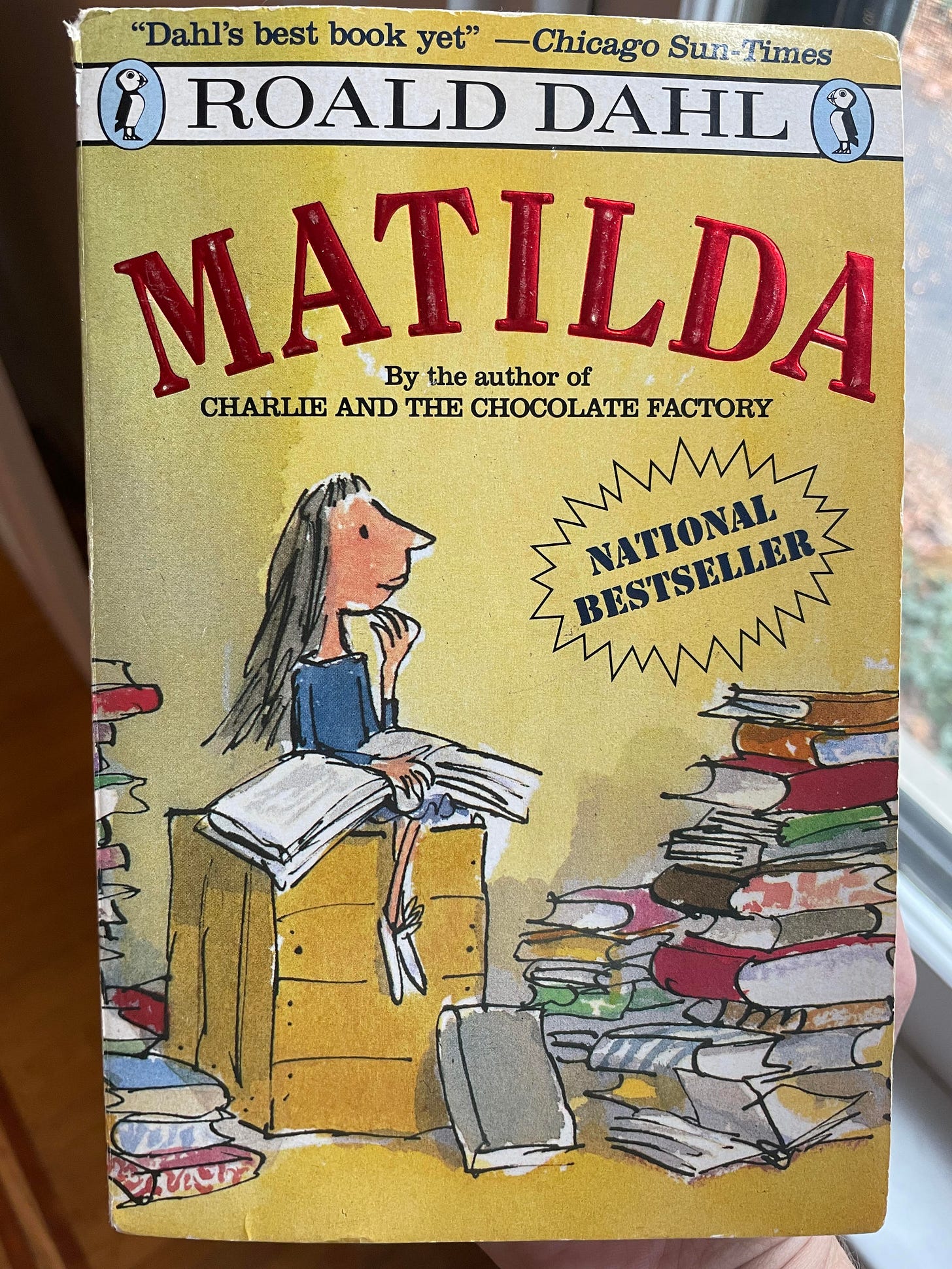

She had a rotten car salesman dad who lied about the mileage of used cars and an absent mother who played bingo during the day instead of spending time with young Matilda. Unlike most children’s books available at the time of my childhood–1989 in a rust belt town–the main character, Matilda, was neglected and emotionally abused, called a twat by her father, told to stop reading books and get herself in front of the telly like a normal child.

In most books I found at my local library–which, like Matilda, I often traveled to alone–the characters, including Ramona Quimby, could be poor but were rich in love. Matilda’s home life was rocky. This was a comfort.

I first read Matilda at my great-grandmother’s apartment, turning pages on one of the many weekends I was supposed to be at my father’s house. I was often, as I saw it then, stuck at my great-grandmother’s house, watching Wheel of Fortune during the day and Golden Girls at night. But magic entered my life when I first read Matilda, the part where she used her mind to make pencils fly. I turned the book over, closed my eyes, and tried. The thought of it made my own mind fly. Of what could be possible for a child. If not pencils. For a child who wanted to change their life. Matilda’s magic was an optimism for a future I was all too happy to believe in; a future out.

Matilda retaliates in the only ways she can. She tricks her father into wearing a glued-on hat. It was delightful to read. She may have been small, but she was able to volley the hurt back at them. I was less interested in this kind of reaction in my real life, and more interested in the family’s disinterest in a child and yet how much a child could become around that disinterest. When she took herself to the library, she became strong, as tall as the tower of books she read.

Matilda entered kindergarten and was quickly considered exceptional. Reading big books and doing complicated math. This, I was not as keen on. Matilda was saved quickly, so certainly, so easily, from the beginning, by Miss Honey, because she was exceptional. This was not attainable for most readers: usually, one is not adopted by a teacher. Not all of us were that exceptional. But had she not been saved by Miss Honey, Matilda could have saved herself anyway. I wanted her to save herself. And that’s the story I’d love to read now.

Even then, and especially now, I would love a book that shows Matilda enduring that childhood with her neglectful family, until she becomes an adult, and got herself out of there. Perhaps the parents would be given sympathy by being given backstories that revealed what they’d endured as children, too. Matilda didn’t need to read Hemingway at four to be deserving of a better home. Plenty of us have quietly stored our nuts and got ourselves into something more tenable in our adulthood. (Though plenty have, sadly, not.)

As biographies of Dahl have come to light, one can see how the author perhaps came to his ability to create villainous characters in part from his own experience. His wife, actor Patricia Neal, nicknamed him Roald the Rotten. He is said to have said racist and anti-Semitic things and created problematic characters he stood behind. For these reasons, I was hesitant to write about Matilda. But that was the kind of book passed along when I was a child: a white man, likely, wrote it. A few years later, I’d watch Poetic Justice, and Maya Angelou’s poems would be the next step towards finding power in a place that originated with harm, but first, there was the proto-power of Matilda, doing what she could, as an isolated child, to grow her internal garden.

It’s my favorite book, can I read it to you? I asked my daughter, a few years ago, when she was five.

We read a chapter a night.

She liked it okay. It did not speak to her as it did me, for reasons I am thankful for – her childhood is not like mine.

What I wouldn’t give to have those weekends with my great-grandmother back now, to be stuck with her. I’d ask her what it was like to work at a factory in Baltimore during WW2 and I’d hope to get the courage up to ask her why she left her daughter back on the farm in West Virginia that she herself had fled. She learned to ride a bike in Baltimore. For a few years, she was free in that big city, and then she was back, parenting her grandchildren, when her daughter and granddaughter-in-law were elsewhere.

Writing this, and thinking of Miss Honey, and my great-grandmother, it occurs to me, just now: maybe I was saved, too.

How long I stared at the pencil on my grandmother’s table. I couldn’t make that physical pencil lift, but I leaned over and through space and time in another way. I could, by moving a pencil across a blank page, make images and feelings appear, as Dahl had. That was what Matilda did for many of us, I think: the book showed us we, too, could have magic. Any of us could have it. We could write.

P.S. For more ways of getting your writing in front of new readers, consider becoming a paying subscriber today.

I love this so much. I hope you are able to write the book one day in which a Matilda type character saves herself.

What a lovely essay. When I read about the moment where you mentioned trying to make the pencils fly with your mind, I had a sudden rush of recognition: I remember doing the same kind of thing as a kid, hoping against hope that I would one day reveal something extraordinary about myself (preferably telepathy or that holy grail, the power to freeze time).