Greetings, fellow Literati!

Today, I’m very pleased to bring you

.Paul writes the

Substack, where he shares life lessons learned during his 30 years working in hospitality. Starting off as a security guard at a hotel in Norway, to giving a speech at the UN Headquarters in New York, Paul has seen it all.Today, he shares the book that made him — A Son of the Circus.

—

On my way to India, I was in the air somewhere over Istanbul when I read the line that changed my life.

"Immigrants are immigrants all their lives".

I had done what I could to fully integrate into my adopted homeland.

Yet, after almost two decades, I still felt foreign when even my best friends introduced me not as a friend or colleague but as "Paul, from Canada."

Why did I have an adopted homeland, you ask?

It all started with a graduation present from my parents. If I could save enough money to sustain myself while out there, they would pay for the flight and a year’s tuition at a Norwegian folk high school.

On a chilly October evening in 1977, I blurted out: “If I’m going to Norway next year, maybe I should start planning.” My mother spent the next eight months reminding me that I was far from mature enough to survive on my own on the other side of town let alone on the other side of the world.

Dad helped me contact the Embassy and search for schools. My older brother received the same graduation present a few years before me and kindly taught me a few Norwegian phrases. My younger brother started planning the redecoration of my bedroom. He would claim it as his own when I left.

When I flew out of SeaTac airport at the end of June 1978, I was still half hungover from partying away my final year of high school. I attended a language camp for North American kids in July and travelled a bit before school started in mid-August.

Days after school started, I was suffering deeply from a hardly-hidden homesickness when I was summoned to the principal's office. There was a call for me. Another person from my hometown was also on a gap year in Norway, at another school.

“I’m going home.”, she said when I picked up the receiver. “I’m homesick and I can’t take this anymore.” Inside my head, voices were yelling, “Tell her you want to go home too!” but they were overshadowed by images of my mother waiting at our local airport triumphantly proclaiming: “I told you so.”

“Say hi to my folks.”, was all I said before I hung up.

As my language skills improved and I had my first close encounters with female Norwegians of a similar age, the homesickness faded and then died.

I extended my gap year and started university. Every six months for six years, university counsellors wrote letters confirming my studies were progressing at a normal rate. The letters allowed me to extend my visa.

Along the way, I got a girlfriend. In 1985, when we weren’t on a break — as we often were — we decided to get married. After that, I didn’t need letters from the university to extend my visa. A half-day at the police immigration office waiting for a three-minute interview was enough. In the bi-annual interviews, I confirmed I was still married and living at the same address as my wife. They stamped my passport and sent me on my way.

Being married also meant I could work. I left university and got a job as a ticket-taker at a movie theatre for a short time. I quit that to take an even lower-paying job as a hotel security guard. While working at the hotel, I became involved with one of the most covert operations in post-WWII Norwegian history. I was part of a very small team planning the state funeral for the king.

Planning began while he was still happily and healthily living in his castle.

Two years of secret meetings which I couldn’t tell my wife about took its toll on our already less-than-perfect marriage. On January 16, 1991, Gulf War I began. The world learned about it live in the famous words of CNN’s correspondent, Bernard Shaw, “The skies over Baghdad are illuminated”.

A few hours later, the phone rang at home. “Blue book is activated.”

Having spent Christmas promising there would be no more secrets, I was less than three weeks into the New Year when I shared the last one with my then-wife.

“I have to go to work. Could you bring a few sets of clothing to the hotel tomorrow? I’ll be home in about ten days. Oh yeah, I guess I can tell you now. King Olav is dead. I’ve been planning his funeral for a couple of years”, I said before leaving.

I spent the next ten days (nights actually) as part of a logistics team ensuring 126 delegations bringing their country’s condolences safely arrived, were housed, and departed the country.

The first thing my now ex-wife said when I returned home and put my feet up in front of the TV was, “I don’t want to be married to you anymore.”

My employees laughed when, just days after the divorce was finalized, a letter came from the police asking me to come to the immigration office. Bring your passport, it said.

At the police station, I was told they had to change my status and I feared the worst. Without another word, the officer simply stamped the passport and handed it back. When I dared to look, it said I had been given extended protection against deportation.

“You’ve been here a long time”, the officer said. “We no longer care if you’re married.”

There was more laughter in the office when I returned to work and told my employees they were stuck with me for life.

I had blue eyes, not-quite-blonde hair, and a Norwegian-sounding name. I spoke the language like a local and even knew who Pompel and Pilt were, but like I said earlier, I still felt foreign in my adopted homeland.

It felt weird every time I was introduced as “Paul from Canada” long after I arrived in the country as an 18-year-old on a gap year. It was as if they were saying, “Don’t share our secrets with him”.

I was the one hiding a national secret.

One day, a former employee of mine got in touch. He’d left to work for a tour operator in Goa, India. “Come visit”, he said.

Intrigued, I spoke to another former colleague, one who now worked as a doorman at a small hotel in London. He was the kind of doorman that could get you anything, anytime. There was a price, of course, but anything anytime included heavily discounted airline tickets. Don’t ask me how or where he acquired them.

I met my mate in a dark corner of Kemble’s Head Pub near Covent Garden. I handed him an unmarked envelope with unmarked bills that added up to an agreed amount. He didn’t open the envelope but handed me an unmarked one of his own. It contained airline tickets. I checked. They were in my name.

We had a pint and then I headed to Heathrow.

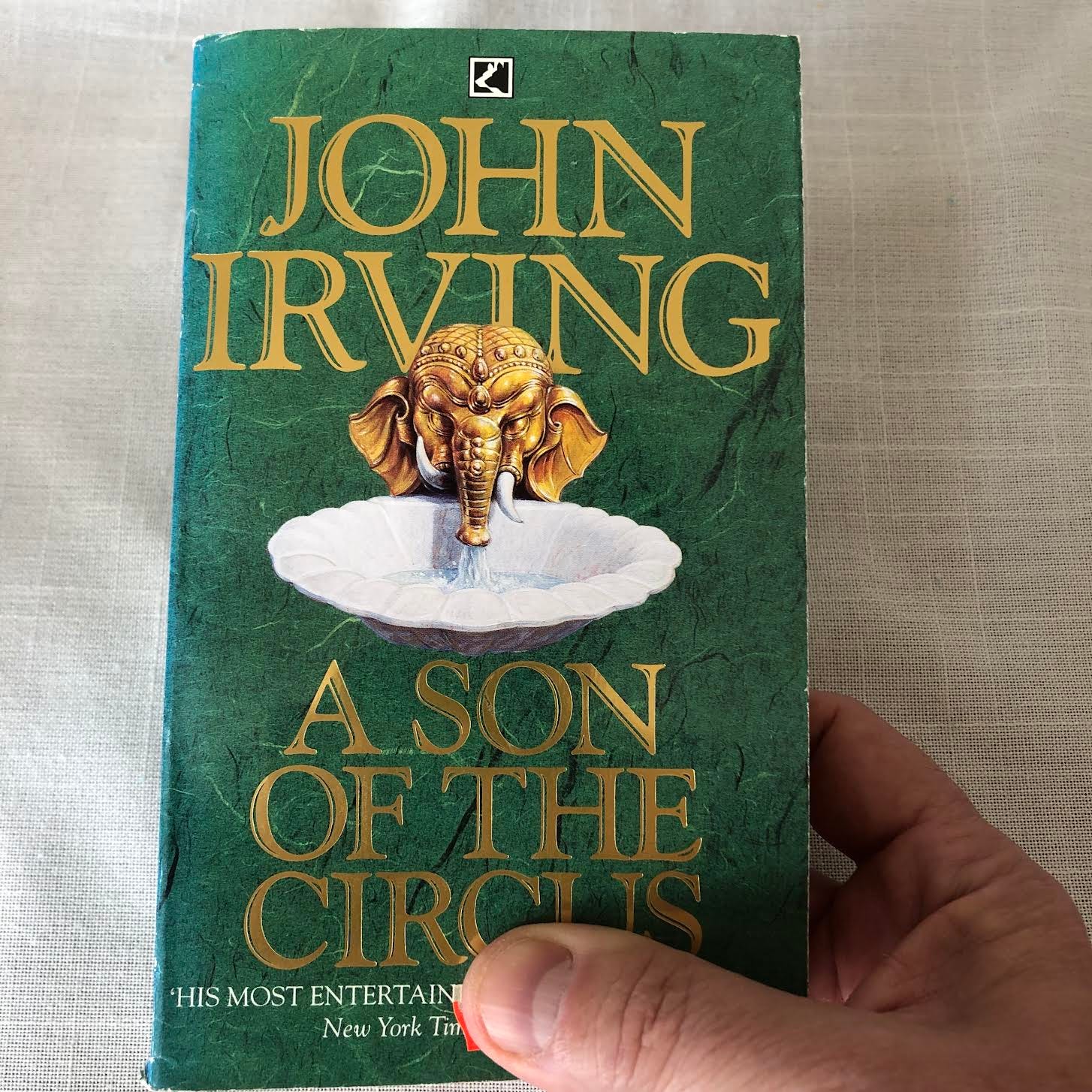

I had been a John Irving fan since one of my landladies had given me her Norwegian copy of Garp. Before departure, I bought his most recent paperback, A Son of the Circus.

We were flying over Istanbul, one of my favourite cities, when I read the sentence that turned the book into the one that changed my life.

In my worn, well-read copy, the quote is near the bottom of page 111.

“‘Immigrants are immigrants all their lives!’ Lowji Daruwalla had declared. It was just another one of his pronouncements, but this one had a lasting sting.”

I knew that sting.

My world changed. Every one of my Norwegian friends and colleagues was Lowji Daruwalla, and I was Farrokh. Later, when I moved to Denmark, Danes became Lowji. I was still Farrokh.

From that day on I knew I would be an immigrant all my life.

I was an immigrant in Norway. I was an immigrant in Denmark.

Eventually I’d been gone so long that I became an immigrant to the country where I was born. Even now, despite having returned here five years ago, I still feel like an immigrant.

Life has brought me full circle.

Friends and neighbours often speak to me like they’re Lowji.

Inside, I still feel like Farrokh.

P.S. If you’d like to write for The Books That Made Us, please see here. For more ways of getting your writing in front of new readers, consider becoming a paying subscriber today.

I feel this deeply, as a Deaf person in a world made by choice to be deeply inhospitable to me. There are islands of rightness and inclusions, but islands only. And honestly? I am an immigrant to these islands also. Thank you so so so much for this.

You are an immigrant as long as you ask yourself the question, but when you stop caring and drawing the line, the dichotomy gets dissolved. How many people are truly at home in their home countries / towns? Being at home or an immigrant is, from a point onwards, just a construct in our minds.