Greetings, my fellow bibliophiles!

Today, I’m very excited to bring you one of my favourite writers here on Substack —

.Kevin writes

— a thoughtful exploration of where Christian thought and world literature meet. Such is Kevin’s knowledge of literature and his mastery of language, that I make sure to never miss an issue.He’s brought both to this essay today, in which he explores a work of that literary giant, James Joyce. Enjoy!

—

I.

Dublin in 2018 was the place to meet James Joyce. I was then an English major meeting the novels I wanted to love. James Joyce was the dead Irishman in the eye patch and glasses who had written scary novels a century before.

Before I arrived in Ireland and had to register for a “Reading Joyce” seminar as my third choice, I thought I preferred the poet W.B. Yeats. The professor of the seminar was a short gray Italian with uncomforting eyes. He told us we would learn how to read Joyce in his class, as though Joyce was a foreign language.

Dublin was all new. A man at the airport held a sign demanding the pope’s arrest. I rode trains from the city to other towns. I read books in parks and pubs. Dublin felt wide open and enclosed, like childhood. The city would be my school, and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man would be my schooling.

Joyce’s novel taught me the two aesthetic styles I needed to write: earnest and thrilling Romanticism, which became playful and generative Modernism. In five sections the novel perfects both at once.

II.

The novel paints its hero, Stephen Dedalus, as he grows from a schoolboy to a young man in late-nineteenth-century Dublin, where such growth was fraught. My professor explained that the novel was a künstlerroman—literally an “artist’s novel” where the (male) protagonist must learn his artistry as he comes of age. The reason we used a German word is because this learning was central to German Romanticism, one of the tradition Joyce decided to fight. One of the earliest künstlerromane was Heinrich von Ofterdingen, written in 1802 by the polymath Novalis. It tells the story of young Heinrich, who becomes a poet during his journey through pre-modern Germany. The typical Romantic, Novalis died young so he couldn’t finish it.

Portrait was a Romantic artist’s novel when I first read it. Its title and final passage declared it: “Welcome, O life! I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.” Here, Stephen welcomes “life” as his muse to the poetic “smithy” inside him. He must go on a journey to encounter “the reality of experience,” so he can make “the uncreated conscience of [his] race” in his soul. By “race,” Stephen refers to the Irish people who needed beauty as they’d never known her before.

Poetic beauty has this passionate intensity in Portrait. Stephen reads The Count of Monte Cristo and then reimagines his Dublin neighborhood as a land of adventure and love. I, too, followed the “veiled autumnal evenings” that led Stephen toward his artistry. The days were cold in Dublin, and the night skies, the sea, were endless while I watched them from buses and trains. Even the sight of them moved me, because I was forging their poetic tributes in my mind.

III.

Stephen’s Catholic faith towers over his poetic soul like a high cathedral ceiling over a candle’s flame. God, with me through Christ’s salvation, similarly looms over my life. Stephen is educated in Jesuit schools at an age when the Church is absolute; he considers entering the vita comtemplativa of the priesthood. He is formed in the Scriptures, schooled in Latin and the pantheon of theologians, and obsessed with the Virgin Mary ever emanating in his visions of Dublin. Stephen’s Catholicism is his culture and aesthetic.

But he also visits prostitutes while a young teenager, and his mortal sins with those women are a lightless, unsettling poetry: “between them he felt an unknown and timid pressure, darker than the swoon of sin, softer than sound or odour.” In his days, he pines in courtly affection for his classmate Emma, she like a poetic symbol of the Beautiful. In his nights, Stephen transgresses his faith by “his brute-like lust” for prostitutes. “Was that chivalry?” his thoughts berate him. “Was that poetry?”

At a school retreat midway through the novel, Stephen and his classmates hear twin sermons on hell which, even though they’re confined within physical pages, feel eternal. The first speech exposits the “exterior darkness,” “awful stench,” “torment of fire,” “company of the damned,” and “the devils” that torment those doomed to hell. The second sermon catalogues “the spiritual torments of hell,” its pains of “loss,” “conscience,” “extension,” “intensity,” and “eternity” which torment them still worse. The sermons ladle horrors and fear over Stephen, but in their repeated additions they are so nearly comic, like an exaggerated tale that seems to stop before the speaker winds up again to explain that there is still more, still worse! Stephen is gripped bodily by “the ravenous tongues of flame,” and he dreams hellish visions of “goatish creatures with human faces.” Only when he confesses his sins to his priest as he’s taught can Stephen dream instead of being “sinless and timid.”

“Another life!”, his relieved rapture claims, and another life does claim Stephen: atheism, determined when he is a university student. I have not done the same. His visceral fear of hell is mine; his exultation in once finding divine beauty is mine also. He, as did Joyce his creator, felt that he needed no constraining heaven upon his wings, no God over his artistic soul. I’ve been blessed to disagree, to nurture what art I may in a soul beneath the Lord. Stephen, my brother, taught me to mourn and love the apostates, who are so often believers too long in pain.

IV.

In Dublin, I wandered. Portrait wanders, imperceptible odysseys all, in its brush-strokes between adolescence and maturity. Dublin Bay is lovely to wander in such a way that Howth Head to the north and Dalkey Island to the south twirl, so that the piers of Dun Laoghaire and the Martello Tower swap places, singing and cyclical, upon the shore. The water of the bay was cold, but I often lowered my hands to it.

Stephen, in the fourth section of Portrait, removes his shoes to walk through the bay at low tide. In movement through the sunned world, he tastes “the call of life to his soul.” He feels his emergence from “the grave of boyhood” as viscerally as he’d felt the fires of hell:

“He was unheeded, happy and near to the wild heart of life. He was alone and young and willful and wild-hearted, alone amid the waste of wild air and brackish waters and the sea-harvest of shells and tangle and veiled grey sunlight and gayclad lightclad figures of children and girls and voices childish and girlish in the air.”

Thus intoxicated, Stephen sees a girl standing in the water, “alone and still, gazing out to sea.” Her skirts are hiked so her thighs become “bared almost to the hips,” but Stephen perceives her as a sign, not as a prostitute. She is the bird-girl whom he gives “the worship of his eyes,” his vision of the world alight with “an outburst of profane joy.” Truly I tell you, Dublin Bay dappled by sunlight is the place to receive this vision and wish you could trust it with your life.

V.

Our professor spent scant time discussing Stephen’s Romantic epiphanies, Catholic de-conversion, or bird-girl manifest, for he bore the revelation of Portrait’s Modernism—the foreign language beneath the lines so convincing in their poetic intensity. He drew our eye to the language and structure of the five sections, their very vocabulary and syntax; because Joyce had treated the novel as artifice for experimentation, we should too. He advanced the language from “a nicens little boy named baby tuckoo” to “the spiritual-heroic refrigerating apparatus, invented and patented in all countries by Dante Alighieri.” Stephen matures throughout Portrait, most nakedly in the words used to render him.

And, by those words, Stephen is artifice that Joyce crafted in the shape of a budding Romantic poet about to bloom. His nature is in the novel’s allusions to the Daedalus of Greek mythology, the “old artificer” whose son Icarus died in foolish flight upon the wings crafted for him. Stephen’s fakeness unsettles my mind even now. How could this boy so like me exist for irony? But Stephen is hapless in his love and ill-formed in his poetry—the gap between his intent and his being, the bed of his sordid realities, leaves him a comic figure.

Is Stephen “unheeded, happy and near to the wild heart of life”? On that page, before he returns in the following section as an intellectualizing layabout trading curses with his parents. What can he write of “the sea-harvest of shells and tangle and veiled grey sunlight” that delighted his soul? Precious little: a villanelle of “enchanted days” that he later spurns, a misremembered verse from the poet Thomas Nashe. Yet Stephen remains grand, taking for himself the Miltonian non serviam against the Catholicism and nationalism he feels like fetters encircling the very wrist he needs to write, taking the Latin absolute even to Paris. Grand to the end, our young Stephen, who needs his mother to arrange his first passage away from home.

All this, I know now, is the comedy of self of many young people. I was ordained into their number in Dublin (if I don’t still preach among them today). And so the novel’s final passage is remade and funnier, once I understand that Portrait is a Modernist novel of ironic play: “to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race” becomes only a wish from the heart, not a vow I can expect Stephen to fulfill. Stephen writes this wish himself— in the final pages of Portrait, his own diary at last overtakes the free indirect third-person that otherwise narrates the novel.

So, too, my pleasure in reading the novel ironically overtook the flame of Romantic wonder it gave me in Dublin. The first doesn’t negate the second. A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man contains multitudes of style, content, and effect, so that it offers the wondrous intensity of the künstlerroman for readers to drink, alongside the playful irony for them to sip. I just find that the novel’s Modernism is the mode I have needed most since I first read it to write (dear Lord, not in Stephen’s vein) from an eye and ear for the expanse inside subtle forms, the generative fun of pouring every word into its own crucible. This pleasure came through the joy of the veiled autumnal evenings that I felt first. Portrait gave me these styles and their maturation in the order and time when I needed them.

P.S. If you’d like to write for The Books That Made Us, please see here. For more ways of getting your writing in front of new readers, consider becoming a paying subscriber today.

A brilliant book indeed. For being as short as it is, it contains so much richness. Joyce's command of perspective is astonishing; the way he can get his readers to see the world through the eyes of his protagonist and not their own (and in the third person no less!) is a course of study on its own; the "Christmas dinner" passage toward the beginning is a fine example of this technique.

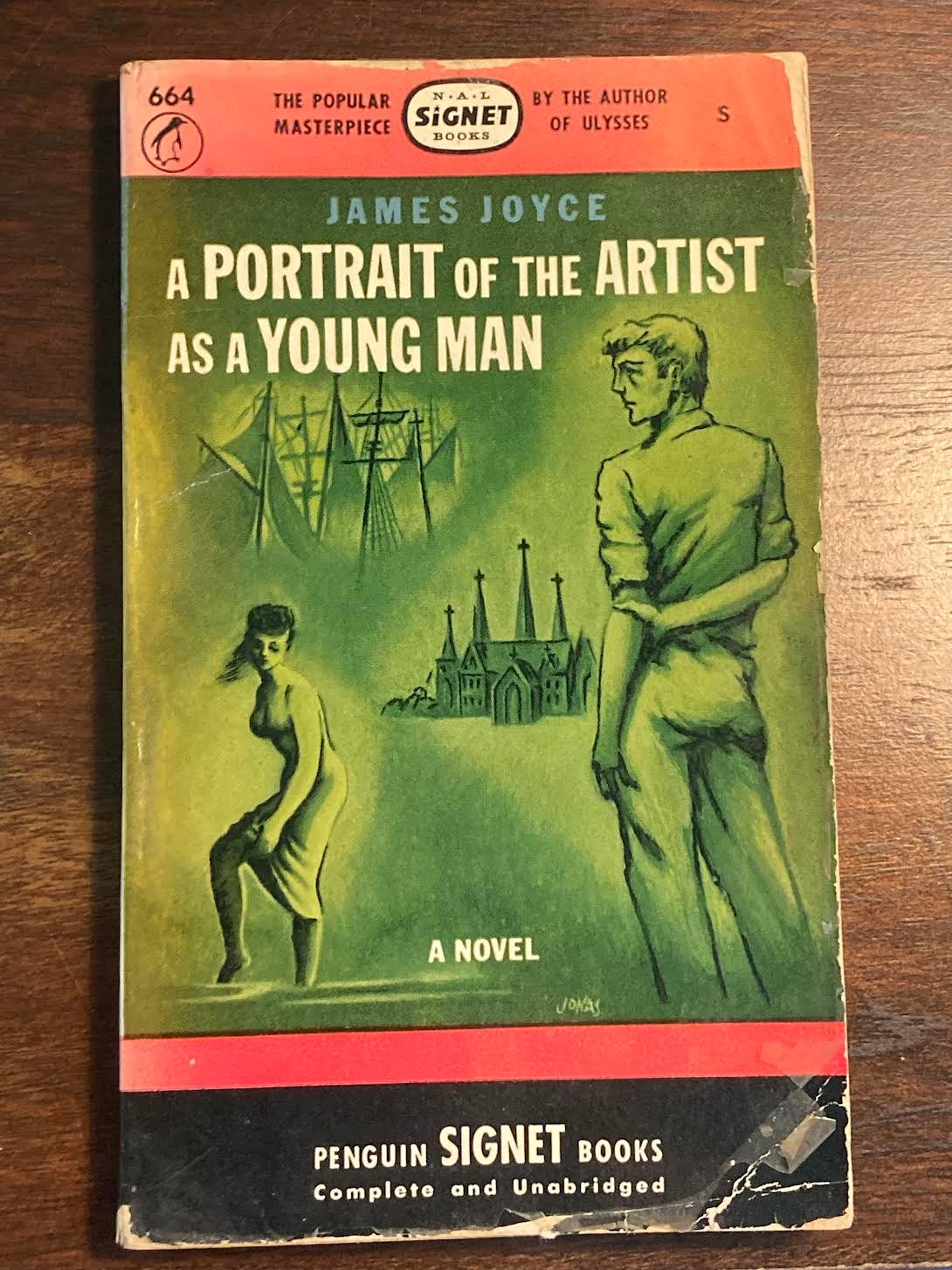

What's the story behind the seemingly-high price for what looks like a rather worn cheap paperback copy of the novel? Does it have a special provenance—signed, perhaps?

Have you read Richard Ellman's biography of Joyce? Very fascinating and definitely worth reading if you're into Joyce.

I've been rereading Joyce this year, so this is great to come across. I wrote about A Portrait earlier this year (https://radicaledward.substack.com/p/a-hole-in-the-floor) and have an essay about Ulysses coming in the next few weeks.

What struck me about reading A Portrait this time was how emotionally resonant I found it, which is something I didn't experience when first I read it.