Booms, Busts, and the Bitter Humor of a Rational Economist

A Tenured Professor by John Kenneth Galbraith

Greetings, fellow readers!

Today, I’m very excited to bring you

.Carrie writes the fierce

, a social and political commentary on the world we live in, what we accept as ‘true' and the media’s role in telling us who we are.What I love about the following essay is the implication that it’s often through fiction that we’re able communicate our greatest truths — even in the case of academic economist. Enjoy!

—

In 1990, just as winter was turning to an early spring in Boston, I picked up a review copy of a book that had been sent to the Middlesex News, where I was working part-time nights and weekends.

A Tenured Professor: A Novel by John Kenneth Galbraith.

A novel?

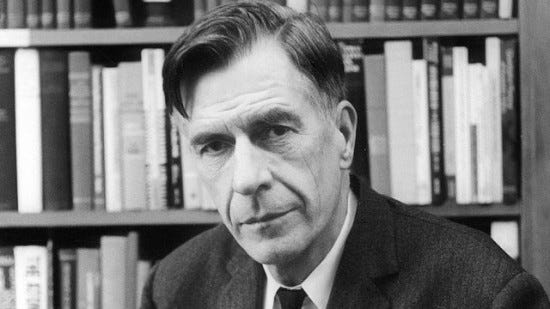

Galbraith had been an economist who advised John F. Kennedy. I had read parts of his seminal economic tract, The Affluent Society, in high school, and he was sort of an idol for me.

“Can I have this?”, I asked the weekend editor.

Two days later, after I had ripped through the first reading of this book, I turned it around and read it for a second time. The only time in my life I’ve ever done that.

I have read it twice since.

A Tenured Professor is about a Harvard economist who invents a computer model to forecast irrational stock market speculation - the Index of Irrational Expectations - or IRAT, in one of the many tongue-in-cheek wordplays Galbraith employs.

The economist has noticed in his studies that capitalist economies have boom and bust cycles, and winners and losers for each one. From the - perhaps apocryphal - tulip mania that crashed Holland’s economy in 1637 “in which a single bulb was sometimes worth more than the farm on which it was grown,” to France’s Compagnie D’Occident which created a bubble by flooding too many shares into land speculation in Mississippi in the 1700s, to the South Sea Bubble, to the 1929 stock market crash, Galbraith’s main character noted one common theme - euphoria that defied reality.

Except for, as Galbraith notes, “a tiny minority” of realists who had been “enriched by the total ruin of all the rest of the people.”

In other words, short sellers. The people who saw the contagious, irrational excitement around a stock or an industry, and knew reality would have to creep back in.

And so, our hero becomes a billionaire (though Galbraith, patrician that he was, does not give a specific number) by finding irrationality around various industries, then betting on the stock going down.

Along the way, with the influence of his wife, the economist posits what might happen if he used his money to do good things. Get rid of homelessness and workplace sexism. Take over defense contractors to change their creative efforts to effect peaceful aims. Create counter political action committees - which Galbraith calls PRCs and takes pains to note the pronunciation as PRiC.

And this is where our hero gets in trouble. It’s OK, in Galbraith’s cynical worldview, if conservative Political Action Committees give money to politicians, but politicians don’t like it when a counter political committee matches dollar for dollar money given to an incumbent, and gives it to his more progressive opponent - thus neutralizing the effect of the original PAC.

This book was written at the dawn of the computer trading age, and well before the Depression-era Glass-Steagall Act was gutted by the Clinton administration, which led to the Enron bankruptcy, to the dot-com bubble and, inevitably, to the stock market crash in 2007/08 that almost put us into another depression.

Galbraith predicts all of this in his book.

Like this passage, when he compares 1980s Wall Street to the “closed-end investment trusts [that] harked back to the great promotions of the 1920s - to Goldman Sachs and the Goldman Sachs Trading Corporation, which in 1929 created the Shenandoah Corporation, which in turn created the Blue Ridge Corporation.”

Then comes the line that, upon rereading in order to write this piece, took my breath away.

“None of these firms toiled to produce goods or render services; all were brought into being to bring a great and special wisdom to speculative success.”

Excuse me? I’m sorry? In the 1920s banks like, oh, let’s say, hypothetically, one called Lehman Bros. created services like, let’s say, hypothetically, mortgage backed securities and collateralized debt obligations, which had no value other than the bets speculators made and caused the world’s financial systems to collapse?

When I read this in 1990, I did not know that 18 years later, that exact scenario would happen. When I read, also about the 1920s, that “portfolio insurance was created to protect the investor from the losses that almost no one expected” I did not envision the hapless and angry employees of AIG, who were suddenly out of work in 2008 because their company insured those worthless speculative CDOs.

I certainly did not envision the post-pandemic era, when investors threw out even the pretense of rational investment as the goal and went straight for the grift - purposefully boosting a stock like GameStop knowing the underlying fundamentals were bad; or preaching the evangelism of crypto, luring people who believed the genius of a guy who gew up at Stanford, and converted their children’s college funds to “virtual tokens.”

Seriously, they gave them the name “virtual,” which means “does not exist” and told people this was the new thing in investment.

I can hear Galbraith laughing.

The first time I went back to this book was at the end of 1996, when the national press went crazy at then-Fed Chair Alan Greenspan’s coinage of the phrase, “irrational exuberance.”

I went straight to my bookcases, in the fiction section, under G, and pulled out this book because I was certain that was the phrase Galbraith - not Greenspan - had coined in describing the economic forecasting model that made his main characters billionaires, and then outcasts.

I was wrong. Only on the exuberance part. Galbraith uses the word, but did not put it together with “irrational.” But what Greenspan was alluding to, Galbraith was screaming through his storytelling.

Just a few years after I first read “A Tenured Professor,” I learned a bit about investing. I loved the idea that you could look at a stock’s share price and its income and do a calculation that gave you a number that told you whether or not it was fairly valued. By the time Greenspan had uttered his words in 1996, I had had numerous conversations on message boards on this new internet invention about how the old way of valuing stocks was passé, and didn’t conform to the new way of doing business.

I did not believe any of it.

The irrationality would last another decade. And when it all came tumbling down, millions of people - many of whom didn’t even own stock - lost everything.

It is not enough to say that this book has solidified for me that Galbraith was a genius. It has also solidified for me that even geniuses aren’t heard. Or believed. I feel like this book was his way of shouting a final warning to “irrational” financial wizards who would, in just a few short years, dismantle everything he had done in his professional life.

You can feel, in this book, the piercing and bitter humor Galbraith was famous - perhaps infamous - for. You will be surprised how much you laugh out loud at the absurdity - which we now know became reality - of the story he was telling.

He also trolls the New York Times. Repeatedly. I cannot tell you how satisfying that is.

A Tenured Professor showed me economics is capable of creating systems that serve all people. And it showed me how hard people in power will work to shut that kind of talk down.

This view has become an underpinning of how I approach writing and journalism. I question the assumptions people make about “that’s just the way it is,” because Galbraith taught me - through this hilarious, 200-page book - that things can be different.

And he taught me what an uphill battle that was.

P.S. If you’d like to write for The Books That Made Us, please see here.

Love this! Had to chime in that the tulip thing is 100% real. Michael Pollan writes about it in his provocative page-turner, “Second Nature,” about plants that have recruited humans to do their bidding. 😁

The great challenge of economics is translating the data into reality. Even in the current situation, the disparity between the narrative and what some of the ramifications presented by various bits of the reported data.

Case in point: we are told that the economy has grown by an annual rate of 2.4% over the most recent quarter, even as private investment and real personal incomes have been trending down. That's a rather hard circle to square.

Communicating these dichotomies to people is a constant challenge.