A.S. Byatt, you will be missed

Possession: A Romance

Dear readers,

Today, we’re including an extra essay in addition to our usual programming. The reason is, sadly, bad news.

The great novelist, poet, literary critic, and short story writer Dame Antonia Byatt, better known as A.S. Byatt, sadly passed away earlier this week. By complete chance, I had been in correspondence with Sarah Harkness about an essay on Byatt’s greatest novel, Possession, for BTMU only the day before. When Sarah offered to write the essay in double-quick-time in wake of the news, I could think of no more fitting tribute to the great author, so famed for her prolificacy.

Sarah writes Advocating for the Ignorant: The Macmillans' crusade where she tells stories from the history of literature and publishing, combining an expert’s eye for detail with the prose of a masterful storyteller. On reading her essay, I’m sure you’ll agree that Sarah’s personal tribute to the late literary genius does the subject full justice.

Just a few days ago, Mikey asked if I would like to write a piece for The Books That Made Us, and without hesitation I pulled my battered copy of AS Byatt’s masterpiece from the shelf and began to re-read and to think and to write. Then yesterday came the unwelcome news that Byatt had died, and this task seemed simultaneously more urgent, more important, and to have more heft, more weight. I needed it to be right, to be the tribute the author deserves, as best and honest as I could make it. I shared my sadness on social media and somehow was not surprised that the reaction from my female friends, and from women I have never met, was immediate and sympathetic. This is a book that has been touching hearts for more than thirty years.

I bought Possession: A Romance in paperback when it first came out, in February 1991, and wrote my name and the date in the front. So, I can place myself precisely – a woman in her late twenties, working ridiculous hours in a City firm, married but with no children as yet, and only time for one distraction outside work, the books I devoured on the commuter train each day. I had turned my nose up at studying English literature when I was just 16, finding the dissection of a text to be frustrating and joy-killing. Now I was free to read what I liked without instruction, and I had happily ploughed my way through the nineteenth century novels loved by my mother, Austen, Trollope and Eliot, and had ventured into the early twentieth century, Waugh, Greene, Forster, Galsworthy. For light relief I read crime, espionage and comedy, but had no time or patience for the self-indulgent ‘modern novel’.

Then in 1990 AS Byatt won the Booker Prize with Possession, and as it seemed to be about Victorian poets, I picked it up and discovered to my huge delight that even though something was contemporary and new, I could still adore it. Then a friend of mine suggested we go to an evening event at the Bishopsgate Institute where Michele Roberts was going to lead a discussion on the prizewinning novel, and I discovered the pleasure to be gained from sitting in a room of enthusiasts all sharing a passion for a book, without feeling the need to tear it apart – and my love of Literature Festivals began.

Possession is the book for book-lovers: it begins with a book, and in a library, the London Library, to be exact:

‘The book was thick and black and covered with dust. Its boards were bowed and creaking; it had been maltreated in its own time. Its spine was missing, or rather protruded from amongst the leaves like a bulky marker. It was bandaged about and about with dirty white tape, tied in a neat bow…Roland undid the bindings. The book sprang apart, like a box, disgorging leaf after leaf of faded paper, blue, cream, grey, covered with rusty writing, the brown scratches of a steel nib. Roland recognised the handwriting with a shock of excitement.’

And thus begins one of the great literary detective novels of all time, as among this trove of scrap paper Roland finds two drafts of a letter from the great poet, Randolph Ash, to an unknown woman, and even in the stiff Victorian prose we can read the beginnings of a passion ‘Since our extraordinary conversation I have thought of nothing else…’

Byatt creates a vivid parallel world of Victorian literary life: the poet Randolph Ash is partly Tennyson, partly Browning. The woman, Christabel LaMotte, is almost Christina Rossetti, but not quite. The two protagonists move in a world peopled with historic characters; Ruskin, Watts, Manet, Darwin. And in the present day she builds a portrait of modern day scholarship, literary critics and academics, University archives that are well-funded (in America) or desperately poor (in England) which I can take as caricature, at times as comic relief, but which I suspect are actually depressingly accurate. And through the quest to uncover the story behind the letters, which becomes a competitive chase, there are two very different stories of love and passion. And, no spoilers here, a final chapter which will surely make anyone cry.

By the time I read the book a second and third time my world was changing: and luckily, because I knew the ending, I now had the time to rejoice in the language, to admire the extraordinary skill which enabled Byatt to create pages of convincing and powerful Victorian verse and Breton folk tale, to appreciate the shifts in time and voice, the build-up of dramatic tension, and the emotional release of the ending. Byatt loves writing about food, she loves colour, she loves textiles and flowers, her scenes are richly decorated, you can bathe in her prose. Again and again, the depths of her historical research are revealed, such as when she follows Randolph Ash across the beaches of North Yorkshire with his nets and collecting jars (just as Charles Kingsley was doing in Devon at the exact same time). Byatt pulled me into a new world, and specifically into the world of curiosity: she was so widely read, she knew so much and made it all so fascinating, that it made me want to follow where she led, understand her allusions, her quotations, her references. I felt that just to know a fraction of what she knew, to follow her down those rabbit holes, would occupy my mind for a lifetime.

But there was more for me personally on later readings: I recognised the urgency of Randolph and Christabel’s need to reach out, to talk, to meet and to give and receive love. The power of a sudden discovery of a new person beyond one’s day to day relationships and routines. I understood the feeling that Roland has that he is living the wrong life, with the wrong person, and that somehow he needs to break the chain, strike out on his own. Possession is about being brave, following one’s heart, and accepting that sometimes the consequences will be hard, tragic even, for oneself or for the people who love us.

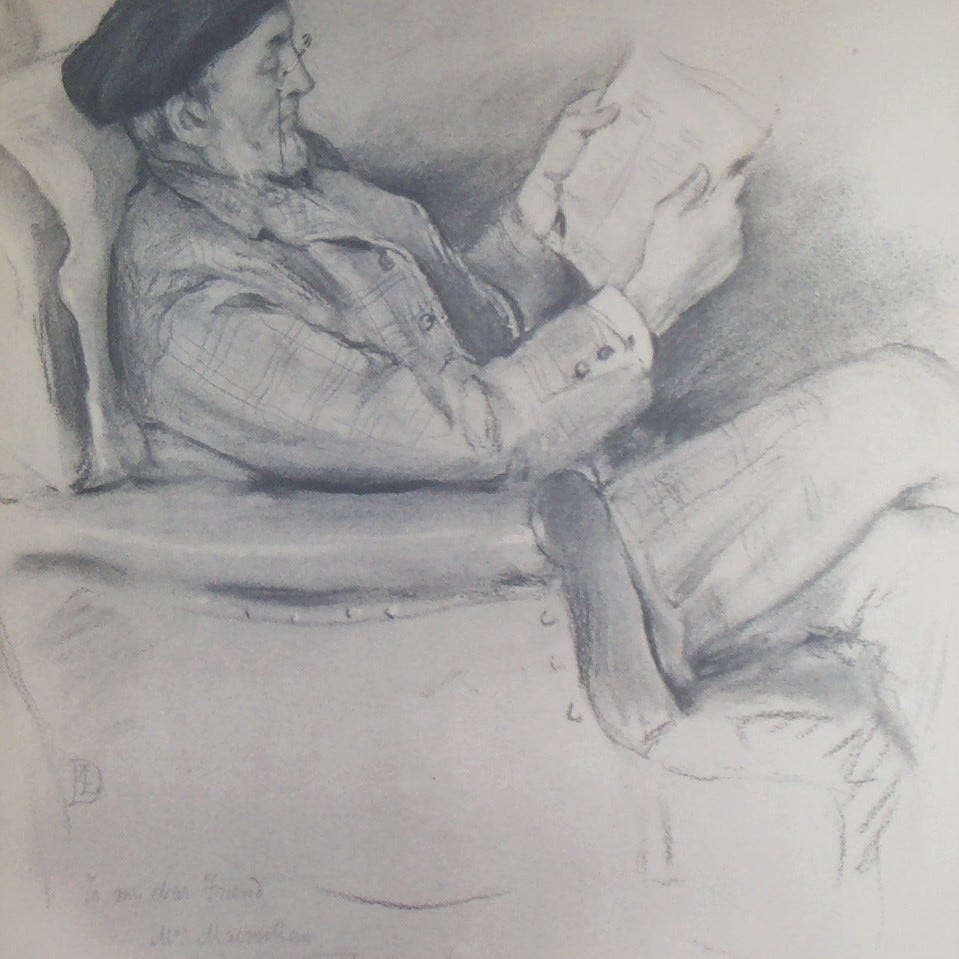

Now as I read Possession again, I am a completely different person: no longer the stressed City girl, or the hungry reader in an unhappy marriage. For the last five years I have myself been immersed in dusty archives, I have worked in the London Library and, for days upon days, in the British Library (but sadly not under the domed ceiling of the old Reading Room where Roland worked), and I have picked my way through the rusty-ink writing and crackling manuscripts of Victorian poets, authors and publishers. I have also uncovered secrets in my researches, and felt Roland’s possessiveness, the simultaneous wanting to share and wanting to keep for myself. My first attempt at writing down something of what I had discovered, to show to others, followed my devouring of another classic work by Byatt, The Children’s Book. Now when I read Possession I know so much more about the world in which Ash and LaMotte are moving: I laughed out loud when I discovered that Crabb Robinson, the man who introduces them in the novel, was a real person and famous literary host, it had seemed such an unlikely name to me in 1991. Reading Possession thirty years ago foreshadowed, and inspired, my current passion for research and biography, my new, fulfilling life.

Towards the end of the novel, Byatt writes: ‘Now and then there are readings which make the hairs on the neck, the non-existent pelt, stand on end and tremble, when every word burns and shines hard and clear and infinite and exact, like stones of fire, like points of stars in the dark … In these readings, a sense that the text has appeared to be wholly new, never before seen, is followed almost immediately, by the sense that it was always there, that we the readers knew it was always there, and have always known it was as it was, though we have for the first time recognised, become fully cognisant of, our knowledge.’

Above all, Possession greets me as an old friend, and it reminds me of difficult times in my life, but each time I return to it I find it says something profound and new about the richness of the written word, and about the sheer joy of reading, and how a great writer can inspire one to read, and read more, and to read again, and again.

Sarah Harkness writes Advocating for the Ignorant: The Macmillans' crusade. She’s writing a biography of Daniel and Alexander Macmillan, to be published by Pan Macmillan in May 2024. Her previous book, Nelly Erichsen: A Hidden Life, was long-listed for the 2019 William MB Berger Prize for British Art History. In 2021 she won The Tony Lothian Prize.

Beautiful tribute. I'm not familiar with the writer and this is the kind of piece that makes me want to learn more.

Your essay is so beautiful. “Possession” has remained at the top of my favorite books -- but I’ve read it (so far) only once, when it was new. I am going to read it again before anything else. Because everything you’ve written is so true. Thank you.