Salutations, bibliophiles.

Today, I’m very excited to bring you

.Natalie writes

, where she shares weekly essays on reading life, common book problems, the crazy things happening in the book world, as well as incredibly fun book reviews. If you like BTMU, I’m sure you’d love Natalie’s work too.Speaking of which, today she’s sharing with us a beautiful essay. She reflects on the book that made her feel less alone after enduring the death of a parent at a terribly young age. Don’t miss this one.

—

When I was 12, a package arrived in the mail.

I can’t tell you what was in it anymore because childhood memories are random and fleeting. While I distinctly remember that Halloween (I was a pumpkin in a giant puffy orange jumpsuit. It was the last year we trick or treated), I can’t remember much about school or how I spent my time.

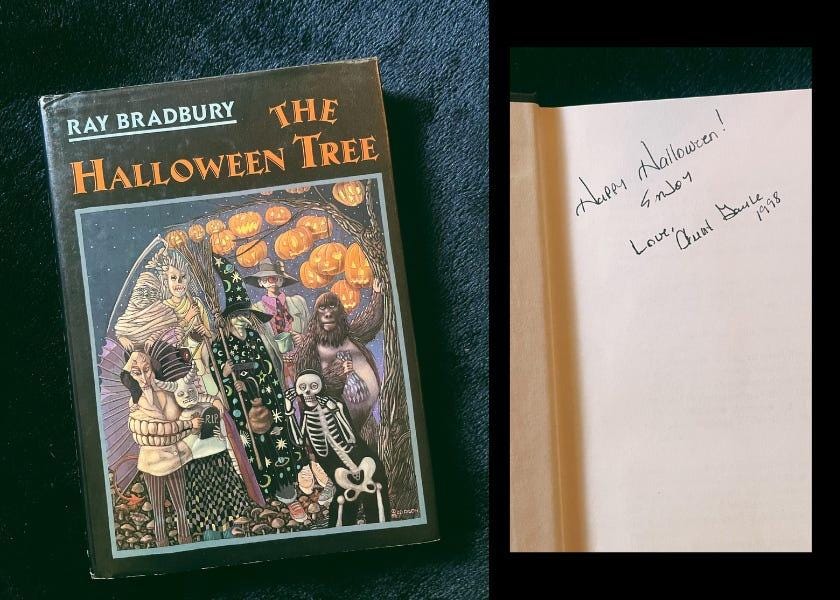

“Happy Halloween! Enjoy. Love, Aunt Gayle - 1998”.

This message inside my copy of The Halloween Tree by Ray Bradbury is how I know that package made it. My aunt was absent except in her book inscriptions. My shelf was full of “Love, Aunt Gayle” - this mysterious woman who rarely came to visit except in the mail. I had met her a handful of times - she lived in Indiana while we lived in California - but again my memory fails at most of these encounters. I have one single memory of her visiting. She took me to the local Borders Books and allowed me to select anything I wanted.

“Any book?” I said, with a hefty $30 hardback edition of Little Women in mind.

“Any book you want at all,” she reassured, her arm sweeping the shelf I had been pacing around for the last half hour.

From my now wise age of thirty-something, I understand why we didn’t see much of her. My father passed away when I was four from lung cancer. And my father was my aunt Gayle’s only blood sibling. There are two most likely reactions when encountering the children of a loved one who has passed. One, a desire to keep them close, to watch their faces for similarities (you have his smile!), to see the loved one alive in the next generation. Or the second, the complete inability to look for fear the despair might seep out and become uncontrollable. My aunt Gayle was the second.

It’s not to say she didn’t love us; her packages assured me of it. She thought of us constantly. But most importantly, she nurtured my love for reading like no one prior or since (my mother, who bankrolled my reading habits for 18 years, might take umbrage with this statement, but alas I speak my truth).

When books from her arrived in the mail, I knew I was in for it. Perhaps a transportation of some sort, a new adventure, a new world, to change the monotony of my suburban life. And they were always something I wouldn’t have selected for myself. As a cautious child, I stuck with what I knew - old favorites like Nancy Drew or The Babysitters Club. Her choices were spectacular and fantastic. The Phantom Tollbooth, the original illustrated The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, The Halloween Tree, all showed up on my doorstep with no explanation, just the inscription: Love, Aunt Gayle.

The Halloween Tree was a revelation. The cover, a group of trick-or-treaters who together created the shape of a skull, promised something dark and sinister. The story dumped you right into the action like dropping into a memory full of mist and shadow. Sentences were complete but felt like ellipses. What was going on here?

In The Halloween Tree, a group of boys head out for the most exciting night of the year. Then as one falls ill with an inexplicable ailment, they must travel through the history of Halloween, guided by the mysterious Moundshroud, to find him before it’s too late. Too late for what is never explained. The boy Pip clutches his side; the light in his pumpkin goes out. Death is vaguely all around. But this is a children’s book!

Children know about death too. Adults know this even when we try to protect them from it. A goldfish from the fair doesn’t last three days, a childhood pet is put to sleep. For me, it was more potent and recognizable, DEATH in all capital letters. My first ever memory is post-funeral, my aunts and mother gathered in the living room, everything shrouded in black. Yet I wasn’t allowed in my father’s hospital room to say goodbye; I wasn’t allowed to attend the funeral. Here I was surrounded by death, but unable to grieve.

When a child loses a parent prematurely, there’s a rip in the space-time continuum. My memory is frozen at a four-year-old’s comprehension. Things rush forward while I stand still. There is no geometry of common sense. My body may be on earth and continues as time ticks on, but it also exists in that very instant forever. A tiny child, unsure of how to manage with a cut bloodline. Over there, a grandparent, an aunt. Over here, a baby brother. Nothing in between.

The Halloween Tree is exactly like that - a vortex of things in the dark rushing as you stand in the middle, still. Pip’s illness threatens to drag his friends out of childhood, the same way I had been suddenly dragged out of mine. The boys fly from the ancient tombs of Egypt to the cemeteries of Dia De Los Muertos, the forward movement of their bodies all that’s needed to master time. But in the end, it is each boy’s sacrifice of time that brings their friend back from the edge of death, trading a year of their lives for Pip’s.

Such a serious task, rescuing a friend from death! There is nothing we can do to protect the boys from the knowledge. Moundshroud, the impervious guide, does not even try. Ultimately, the book suggests that we shouldn’t. Let the children learn and face it, so they may understand rather than cower in the unknown. The Halloween Tree reflected a deep-seated fear I didn't know was brewing in me - that everyone I ever knew would die. But it also suggested that even if it did (and would!) happen, I would be alright.

Night and day. Summer and winter, boys. Seedtime and harvest. Life and death. That’s what Halloween is, all rolled up in one. Noon and midnight. Being born, boys… racing through thousands of years of death each day and each night Halloween, boys, every night, every single night dark and fearful until at last you made it and hid in cities and towns and had some rest and could get your breath.

I cannot say whether back in 1998 my Aunt Gayle selected The Halloween Tree for any specific purpose. I loved Halloween, but by that time, I was watching my childhood in a rearview mirror. She most likely did not know what that book would mean to me, how it would reflect my deepest fears, cleansing me of isolation for a few moments.

So much of what I write about now in my Substack and beyond is a reflection of my early reading years. By exposing me to new and wild ideas, I was able to imagine a world bigger than mine. Her contribution to my formation as a person, a reader, and an artist is cemented in time. And I will be forever grateful.

P.S. For more ways of getting your writing in front of new readers, consider becoming a paying subscriber today.

Wonderful essay. I love how your writing itself weaves and transcends time.

Natalie this is 10/10 - tender and emotive.